In December 2013, a delegation from Nanjing University (NJU), led by CCP Party Secretary Ren Lijian (任利剑), toured the United States and Canada to expand alumni networks and build “technology transfer” partnerships with Western universities. One key stop was George Washington University (GWU), where the delegation met with senior administrators to exchange experience in alumni development and international cooperation on 16th December 2013. One of them was Michael Morsberger (Feb 2010-Oct 2024), vice president for development and alumni relations at George Washington University. Li-Jian Ren was also the Vice President of GENERAL ALUMNI ASSOCIATION OF NANJING UNIVERSITY.

At first glance, this seemed like a routine academic exchange. However, historical and institutional records reveal deeper implications tied to China’s Military-Civil Fusion (军民融合) strategy.

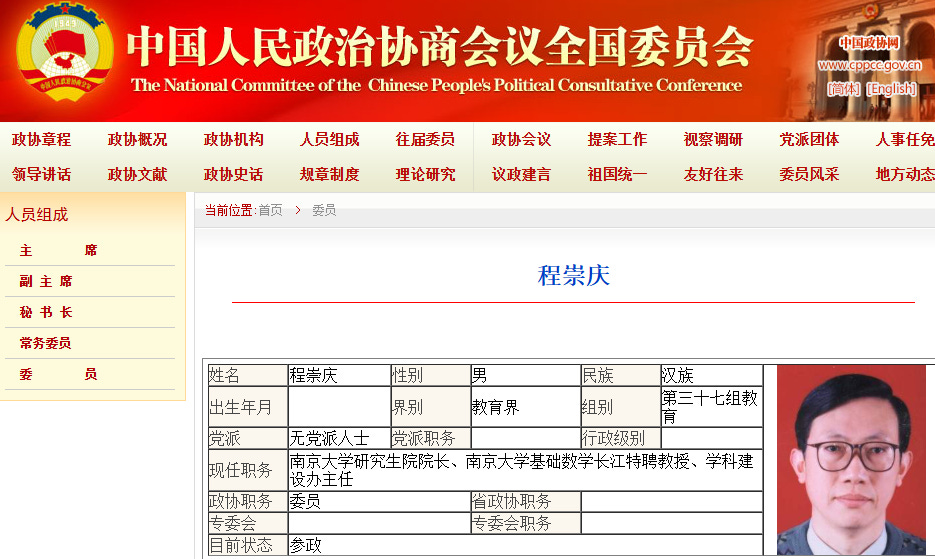

From April 6–11, 2013, a delegation from Nanjing University (NJU) led by CCP Party Secretary Hong Yinxing(洪银兴) visited the United States. The highlight of the trip was the inauguration of the Confucius Institute at George Washington University (GWU) on April 10, 2013. Secretary Hong, accompanied by NJU Vice President Cheng Chongqing(程崇庆), a Member of the Standing Committee of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference(CPPCC) and Vice Chair of Jiangsu Committee of CPPCC promoting the CCP’s united front work, attended the ribbon-cutting ceremony along with Xu Lin (许琳), Director General of China’s Confucius Institute Headquarters (Han ban or Han Office), and GWU President Steven Knapp. In his remarks, Secretary Hong delivered a keynote speech representing NJU, while all parties participated in a roundtable discussion reviewing past cooperation and exploring future collaborations between NJU and GWU.

President Knapp, a longtime acquaintance of Secretary Hong dating back to his tenure as Provost at Johns Hopkins University, emphasized the significance of the collaboration. The GWU Confucius Institute is China’s first in Washington, D.C., and NJU’s eighth overseas Confucius Institute. GWU allocated a dedicated three-story building on campus for teaching and administrative purposes, reflecting the high level of attention both from the Chinese government and the university to this joint educational initiative.

Hidden Political Roles Behind Nanjing University Leadership

Cheng Chongqing, officially listed as Vice President of Nanjing University and Professor of Dynamical Systems, has a distinguished academic record:

Led multiple National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) projects, including major and key programs.

Awarded the 2001 National Natural Science Second Prize as first author.

Invited speaker at the 2010 International Congress of Mathematicians.

Served as President of the Jiangsu Mathematical Society and expert reviewer for the State Council Academic Degrees Committee.

However, official NJU reporting omits his significant political roles:

Vice Chair of the Jiangsu Provincial CPPCC

These positions place Cheng directly in China’s United Front Work system, which the CCP uses to influence domestic and international institutions. His dual identity—as a leading scientist and a high-ranking political appointee—illustrates how top Chinese academics can simultaneously serve key party-state agendas, a point often obscured in outward-facing university communications.

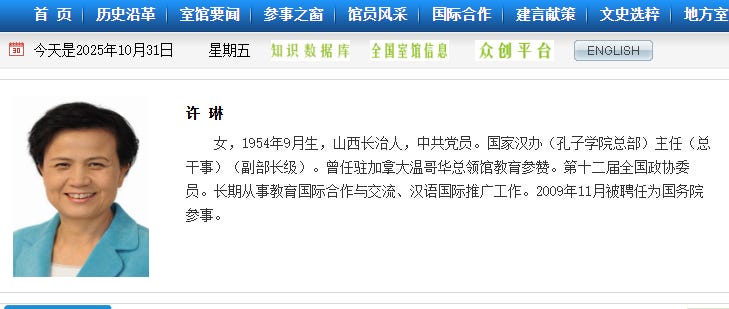

Hidden Political Dimensions of Xu Lin’s Career

Xu Lin (female, from Changzhi, Shanxi) is officially known for her leadership of the Confucius Institute network, but her broader political profile is rarely emphasized:

Chinese Communist Party member

Former Director/Executive Director of Hanban/Confucius Institute Headquarters (vice-ministerial level)

Education Counselor at the Chinese Consulate General in Vancouver, Canada

Member of the 12th National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC)

Counselor of the State Council of China

These roles place her squarely within the CCP United Front apparatus, responsible for managing overseas cultural influence and educational engagement. Public-facing reports focus on her Hanban/Confucius Institute leadership, but her political appointments and advisory positions show a dual role: advancing Chinese soft power abroad while serving high-level CCP policy objectives.

Source: Official biography(link)

December 2013: Nanjing University and George Washington University Formalize Confucius Institute Partnership

On December 10, 2013, Nanjing University (NJU) President Chen Jun met with George Washington University (GWU) President Steven Knapp and his delegation in Nanjing. The two university heads held in-depth discussions on the development of the Confucius Institute and scientific cooperation, and formally signed the Confucius Institute agreement between NJU and GWU.

Attending the meeting were Pu Lijie (Assistant to the President) and officials from NJU’s Overseas Education College and Office of International Cooperation and Exchanges.

President Chen Jun congratulated Knapp on being elected Chairman of the Confucius Institute U.S. Center Council. He emphasized that the jointly established Confucius Institute represented “the fruit of joint efforts between both universities,” expressing gratitude for GWU’s support. Chen proposed expanding collaboration through the Confucius Institute platform—particularly in areas such as low-carbon city development, sustainable water resources, air pollution, and soil safety—to address “environmental and human habitat challenges caused by rapid economic growth.”

Knapp responded positively, pledging to strengthen the partnership. He noted that the Washington, D.C.–based Confucius Institute enjoyed “a unique geographical advantage” and could become a key hub for the program’s U.S. growth. Knapp endorsed Chen’s sustainability proposals and outlined GWU’s research achievements in urban sustainability, calling for “broader, deeper collaboration across multiple fields.”

Following the meeting, Chen Jun and Knapp formally signed the Confucius Institute agreement on behalf of their respective universities.

Earlier, on December 9, NJU Vice President Cheng Chongqing (also a CPPCC Standing Committee member and vice chairman of the Jiangsu Provincial CPPCC) attended the NJU–GWU Confucius Institute Board meeting, where both sides discussed long-term strategic planning. Later that afternoon, NJU CCP Deputy Secretary Ren Lijian met briefly with the GWU delegation, including Knapp and Vice President Morsberger, exchanging views on alumni and development cooperation.

During the April 2013 inauguration of the Nanjing University–George Washington University Confucius Institute in Washington, D.C., media coverage highlighted not only high-level participation from NJU Party Secretary Hong Yinxing, Vice President Cheng Chongqing (a CPPCC Standing Committee member), and Hanban/Confucius Institute Headquarters Director Xu Lin (a State Council Counsellor and senior CCP official) — but also featured a George Washington University biology student, illustrating how the Confucius Institute directly integrated with U.S. STEM education.

“Qi Siyuan, a senior majoring in biology at George Washington University, had studied Chinese for three years and participated in summer programs and fieldwork in Shanghai. Deeply fascinated by China, he planned to shift his academic focus after graduation — to study linguistics at Georgetown University — and hoped to further improve his Chinese at the newly established Confucius Institute on his home campus.”

At the ribbon-cutting ceremony, GWU President Steven Knapp emphasized that the Confucius Institute would serve not only the university’s own students and faculty, but also “aspiring professionals from Washington-based institutions such as the World Bank and the U.S. Department of State, offering them a bridge to learn Chinese and understand Chinese culture.” He also praised ongoing cooperation with Nanjing University and other Chinese universities, stating that the program would “foster greater mutual understanding between the peoples of both countries.”

However, what official Chinese reports framed as cultural exchange carries deeper implications when placed in context:

The involvement of biology majors and scientific exchange language programs reflects how the Confucius Institute structure enabled access and trust-building across academic and technical fields — not only humanities.

Nanjing University’s School of Medicine, a known hub for civil–military fusion (军民融合) research, was already engaged in joint projects with defense-related labs under the Ministry of Education and the PLA medical system during the same period.

The result is a revealing alignment:

Cultural diplomacy on the surface, but beneath it, a channel connecting biomedical research talent, political United Front figures, and Western academic institutions — centered on Nanjing University’s Confucius Institute network.

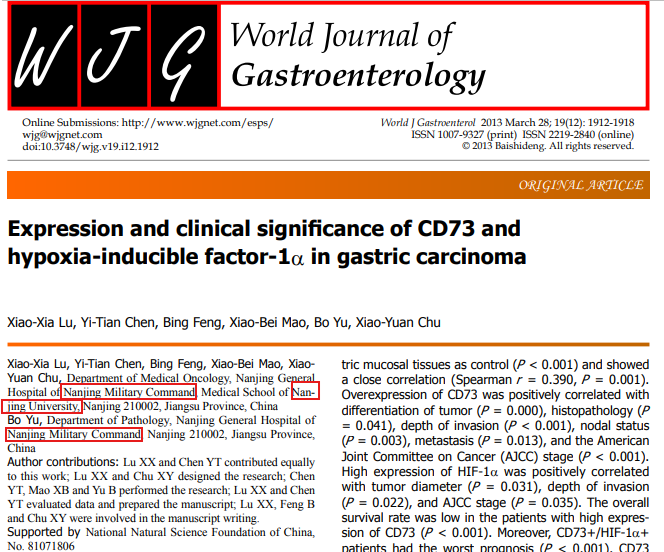

The Military Backbone: NJU and the PLA Nanjing Military Command(中国人民解放军南京军区)

Multiple peer-reviewed studies list dual affiliations between NJU’s Medical School and the Nanjing General Hospital of the PLA Nanjing Military Command — a top military medical and research institution. For example:

“Expression and clinical significance of CD73 and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in gastric carcinoma” (Xiao-Xia Lu et al.) identifies authors as members of Department of Medical Oncology, Nanjing General Hospital, Nanjing Military Command, Medical School of NJU.

“Restricted intravenous fluid regimen reduces postoperative complications” (Tao Gao et al.) lists identical dual affiliations.

These collaborations are longstanding: as early as 2010, the PLA Nanjing Military Command General Hospital and NJU co-organized academic symposia to merge basic science and clinical military medicine, researching topics from cellular mechanisms of seasickness to antibiotic-resistant “superbacteria.”

Even the medical school’s historical roots reinforce its military integration: originally National Central University Medical College, it was transferred to the PLA system in 1951. Though “reestablished” under the Ministry of Education in 1987, it remains heavily intertwined with PLA Nanjing Military Command General Hospital for teaching, research, or clinical operations.

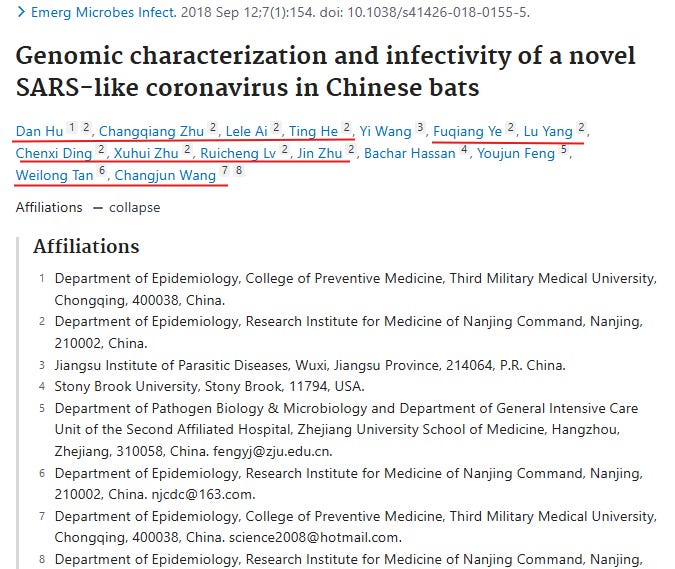

Connections to COVID-19 Pandemic Research

A critical example of this dual-use research comes from the 2018 paper “Genomic characterization and infectivity of a novel SARS-like coronavirus in Chinese bats” (Hu et al., 2018, Emerg Microbes Infect, DOI: 10.1038/s41426-018-0155-5). The study sequenced Zhoushan bat coronaviruses ZC45 and ZXC21, considered the closest known relatives of SARS-CoV-2 at the time.

Most authors were affiliated with the Research Institute for Medicine of Nanjing Military Command, Nanjing, directly under PLA control, and Third Military Medical University, Chongqing.

Crucially, the Nanjing Military Command’s Institute of Military Medicine is the primary institution behind the Zhoushan bat coronavirus strains ZC45 and ZXC21, widely cited by Chinese government officials, including some Chinese Communist Party(CCP) members, as the closest known relatives of SARS-CoV-2 in their papers. Dr. Li-Meng Yan, a well-known coronavirus scientist who previously worked at a WHO reference lab, also held the opinion of Chinese government officials that Zhoushan bat coronavirus strains ZC45 and ZXC21 are the closest known relatives of SARS-CoV-2.

This is not “foreign smearing.” These findings are documented in government-funded studies by Chinese government researchers, some of whom are Chinese Communist Party members, establishing a direct PLA link in early coronavirus research. The Wuhan Institute of Virology is often cited in Western media, but the PLA’s Nanjing Military Command research is likely the real foundation for these bat coronavirus sequences.

This demonstrates that the military medical system, not civilian labs alone, led foundational research on SARS-like bat coronaviruses — contradicting narratives that these discoveries were purely civilian scientific work. It also underscores the dual-use nature of the research, as PLA institutions routinely conduct both medical and strategic biosurveillance studies.

Implications of the 2013 GWU Visit

When NJU delegations visited GWU and other U.S. institutions:

They were not merely conducting alumni outreach; they represented a civilian-military hybrid embedded in PLA research structures.

Collaboration opportunities, including “technology transfer” discussions, could indirectly advance dual-use research under the guise of academic exchange.

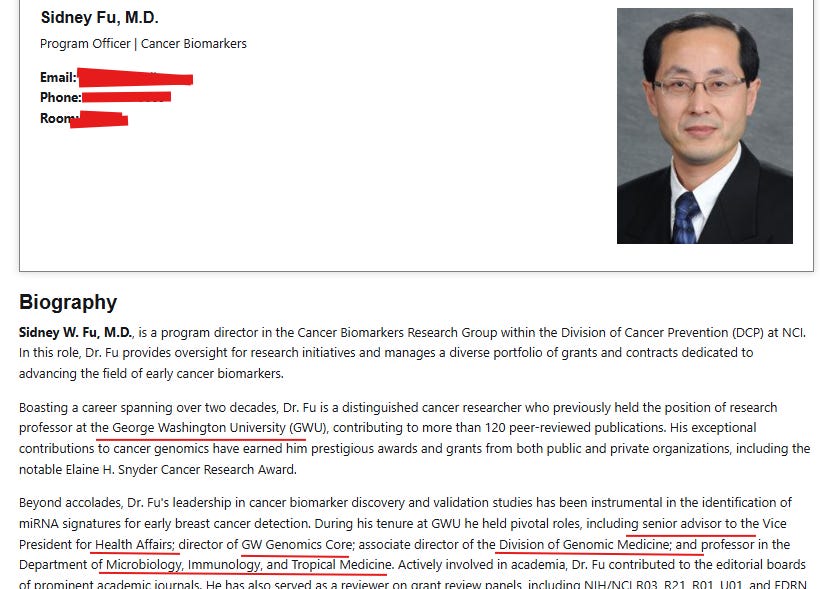

Figures at GWU, such as former White House Physician Kevin O’Connor, were connected to advisors like Sidney W. Fu (Fu Sìdōng/傅四东), who held senior roles in GWU’s medical and genomics programs while also acting as a mentor in the International University Innovation Alliance (IUIA) — a Chinese government-supported platform tied to military-civil integration.

Military-Civil Fusion and Global Innovation Networks

The NJU-GWU partnership illustrates a broader pattern:

Leveraging academic diplomacy to expand PLA-linked research cooperation.

Embedding dual-use research (e.g., oncology, genomics, virology) within international collaborations.

Creating overseas legitimacy for institutions tightly bound to CCP military medical structures.

Platforms like the IUIA connect Western universities with Chinese ministries and companies closely affiliated with the PLA and the United Front Work Department, potentially channeling sensitive research back to military-aligned programs.

From Nanjing University Chemistry to Washington Biomedical Engineering

One telling example of Nanjing University’s scientific diaspora within the U.S. capital’s research ecosystem is Dr. Luyao Lu (陆路遥), currently an Associate Professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at George Washington University (GWU) — the same university that partnered with Nanjing University (NJU) to establish a Confucius Institute in 2013, just blocks from the White House.

Lu received his B.S. in Chemistry from Nanjing University in 2010, followed by a Ph.D. in Chemistry from the University of Chicago in 2015 under Professor Luping Yu. He then completed postdoctoral work at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign (2015-2016) and Northwestern University (2016-2018) with John A. Rogers, a pioneer in flexible and bio-integrated electronics. In 2018, Lu joined GWU as a tenure-track assistant professor (later promoted to associate professor), leading a research group developing organic/inorganic flexible semiconductors and implantable bioelectronic devices.

Chinese-language recruitment advertisements for his GWU lab — distributed through PRC academic channels — explicitly invite Ph.D. and postdoctoral applicants from biomedical engineering, electronics, materials, and chemistry backgrounds, encouraging “joint training” (联合培养博士) with Chinese universities. The postings frame the lab as a conduit for biomedical and flexible electronics collaboration between U.S. and China-based researchers.

“Our group focuses on flexible semiconductor functional materials and devices, as well as their applications in wearable and implantable biomedical systems, to provide new technological tools for biomedical development.”

— Luyao Lu Lab recruitment statement (in Chinese)

The overlap is striking:

Nanjing University alumni occupy posts inside George Washington University’s bioengineering department, within walking distance of U.S. federal agencies such as NIH, NIST, and NSF — all explicitly mentioned in Chinese recruitment ads as local partners.

The research focus — implantable and wearable biosensors, flexible semiconductors, and organic electronic interfaces with living tissue — sits squarely within the domain of dual-use biotechnology with implications for health monitoring, neuro-interfaces, and defense biosensing applications.

The continuity of affiliation, from NJU chemistry to GWU biomedical engineering, mirrors the institutional partnership that began with the 2013 Confucius Institute inauguration and later expanded through joint NJU–GWU scientific exchanges.

In the broader context of the PLA’s civil–military fusion (军民融合) strategy and Nanjing’s historic military medical research system, Lu’s academic trajectory exemplifies how ostensibly civilian scientific exchanges can converge with fields of strategic biomedical technology — especially when embedded within politically sensitive university partnerships in Washington D.C.

🧩 The Scholarship That Wasn’t: CSC as a Research Data Collection System

CCP-Supported Overseas Talent Pipeline

Luyao Lu’s case also reveals how the CCP regime’s “self-financed” scholarship programs quietly extend its control networks across the global academic sphere.

In 2014, while pursuing his Ph.D. at the University of Chicago, Lu received the Award for Outstanding Self-Financed Students Abroad (国家优秀自费留学生奖学金) — administered by the China Scholarship Council (CSC) under the CCP Ministry of Education, and approved by the State Council of the People’s Republic of China.

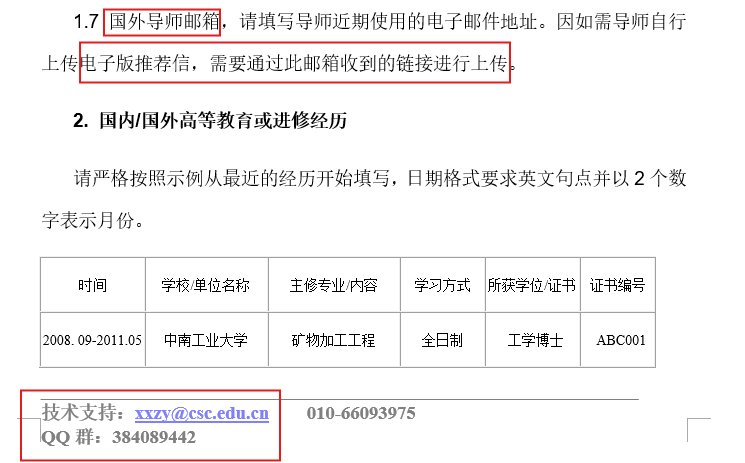

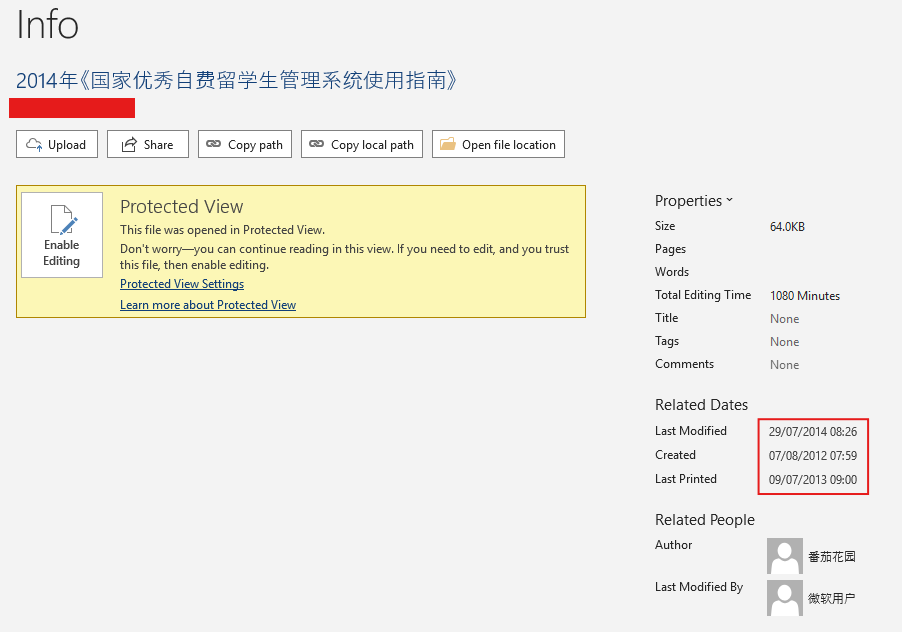

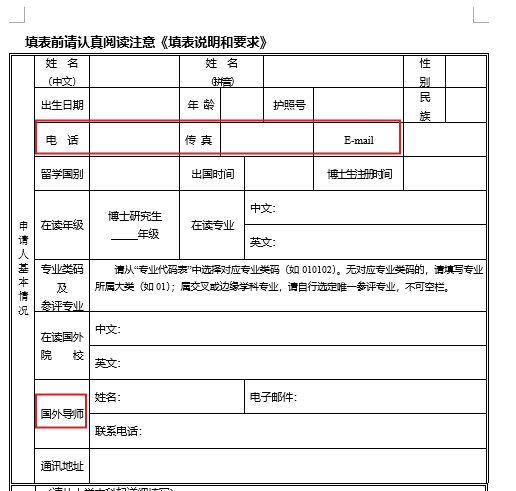

Although publicly framed as a merit-based grant, the program serves as a CCP regime–controlled loyalty and intelligence-gathering mechanism. The application manual (2014 User Guide to the National Management System for Outstanding Self-Funded Overseas Students) — system metadata shows it was created in 2012, modified in 2014, and last printed in 2013 — requires candidates to upload their personal data, contact address, research details, and supervisor contacts. Official support emails (xxzy@csc.edu.cn) and QQ group IDs (384089442) further expose how integrated the system is with the CCP’s domestic digital infrastructure.

Applicants must print and deliver the full dossiers to CCP embassy education offices, where all materials are archived for political vetting. This process enables the regime to track thousands of overseas PhD candidates, mapping global scientific talent and embedding loyalty assessments into supposedly independent academic programs.

Beyond surveillance, the program poses deeper risks. The detailed personal data — including contact addresses — provide potential vectors for targeted harassment, coercion, or even physical threats by pro-CCP networks or the regime’s overseas police stations. At the same time, the data pipeline gives the CCP opportunities for technology acquisition, intellectual property theft, and united front influence — including pressuring scholars abroad to shape narratives favorable to the CCP, or suppress research and news that might embarrass the regime.

What appears to be an academic scholarship is, in reality, part of a global architecture of CCP political control, talent mapping, and information manipulation operating under the cover of “education exchange.”

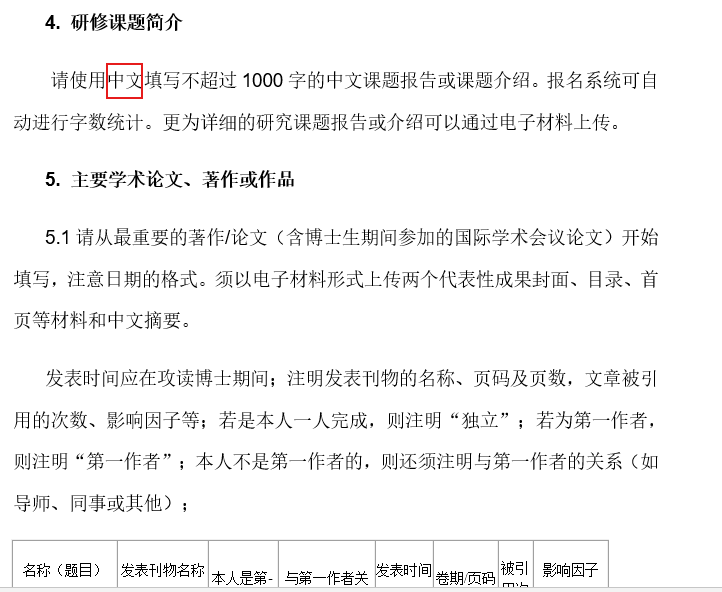

While Beijing publicly described the Chinese Government Award for Outstanding Self-Financed Students Abroad as a scholarship to “recognize excellence,” the actual application form reveals a far more intrusive structure. Each applicant was required to submit:

Full publication history — listing all papers, journals, authorship rank, impact factors, and citation counts;

Two representative works — including scanned covers, tables of contents, and the first page of each article;

Proof of international conference participation — with invitation letters attached;

A 1,000-character research topic report in Chinese, describing the applicant’s ongoing PhD research in detail.

In short, the award application functions as a standardized research intelligence form. Every Chinese PhD student abroad effectively hands over to Beijing:

their entire academic output, collaborators, institutional affiliations, and active research direction — all translated into Chinese for central archiving.

The form even requires the foreign supervisor’s full name, phone number, and email address, allowing the PRC’s education offices attached to embassies (often operating as United Front nodes) to map Western research ecosystems directly.

The form’s 2010 edition aligns with a broader wave of educational-military integration:

the Hanban–Confucius Institute expansion under Xu Lin;

the CSC–Ministry of Education merger of overseas personnel tracking systems;

and the PLA’s acceleration of dual-use biotechnology under the Nanjing-based military medical complex that later produced ZC45/ZXC21.

Thus, this “scholarship” was not a benign grant — it was an institutionalized mechanism to harvest research data and personnel profiles from overseas Chinese scientists, while grooming them for reabsorption into China’s military-civil fusion programs.

Digital Espionage Disguised as a Scholarship System

The CCP regime’s so-called scholarship system is not just a bureaucratic formality — it is an engineered data-harvesting pipeline.

Applicants must register through an online portal operated by the China Scholarship Council (CSC) — a body directly under the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (later referred to as the CCP regime) since 2014.

The application requires full disclosure of:

Passport information and contact address,

Academic transcripts,

Research topics and abstracts,

Supervisors’ names,and emails

Lists of conference invitations and publications.

All of this is uploaded through a CCP-controlled system, timestamped and geolocated. Once centralized, the data can be mined for intelligence value — identifying high-value targets such as:

Professors tied to US defense or space research,

Laboratories with dual-use technology potential,

Overseas students positioned near strategic research networks.

This digitized process enables mass-scale big-data profiling. By cross-referencing submissions with open-source research and internal CCP databases, the regime can map foreign R&D ecosystems in real time.

The result: the CCP can instantly pinpoint which lab works on aircraft carrier systems, or which supervisor advises someone like Anthony Fauci, and then deploy tailored influence or recruitment efforts through United Front operatives or so-called “education counselors” embedded in embassies.

What looks like a scholarship portal is, in practice, a data-driven espionage infrastructure — a quiet yet powerful instrument for the CCP regime’s scientific infiltration and elite capture strategy.

🧬 Link to the NJU–GWU Chain

The connection becomes visible when we trace alumni trajectories:

Luyao Lu (Nanjing University → University of Chicago → GWU) received this “Outstanding Self-Financed Student Award” in 2014 — during the same period when NJU’s medical departments were conducting joint virology projects under dual-use frameworks;

GWU’s Biomedical Engineering department, where Lu now leads a bioelectronics lab, sits within walking distance of NIH and the World Bank — institutions explicitly referenced by GWU’s own Confucius Institute as “target audiences” for Chinese-language and cultural outreach;

Several GWU biology students publicly described studying Chinese via NJU-linked Confucius Institute programs, mirroring the same “exchange + data collection” model.

Together, these strands show how the NJU–GWU exchange framework — originally couched in “language and culture cooperation” — overlaps directly with CSC-linked data capture pipelines and dual-use biomedical interests.

In recent years, the intertwining of Chinese military-linked research institutions with prominent U.S. universities has raised serious questions about the scope and impact of these collaborations. Central to this network are figures tied to the PLA’s military medical system, military-civil fusion initiatives, and international academic programs.

One striking example involves Xi’an Jiaotong University’s Second Affiliated Hospital, He Xijing, BGI (华大基因), and George Washington University (GWU), which had significant influence over US Veterans, US Whitehouse and Joe Biden.

One key figure is Qin Chuan, who plays a pivotal role in China’s military-civilian integrated research ecosystem. Qin has collaborated with multiple PLA-linked research entities, including Xianzhu Xia, a specialist in zoonotic and veterinary military research. Their work aligns with broader PLA interests in bio-warfare and pathogen research. Additionally, researchers involved in Zhoushan bat coronavirus studies maintain dual appointments at the Army Military Medical University, further integrating military priorities with civilian scientific inquiry.

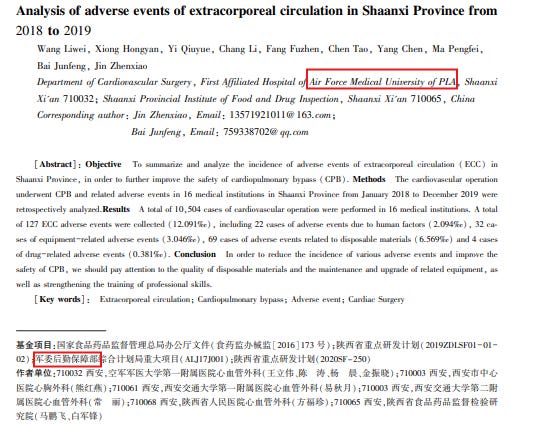

In 2015, a delegation from the George Washington University (GWU) School of Medicine visited Xi’an Jiaotong University’s Second Affiliated Hospital (XJTU 2nd Hospital). The visit was personally invited by XJTU 2nd Hospital Dean He Xijing(贺西京) , a core figure in China’s military-civilian biomedical programs, whose hospital carries multiple projects funded by General Logistics Department (ALJ17J001 and others) of the CCP Central Military Commission.

The discussions centered on youth physician training, graduate research collaboration, and joint project development—directly embedding PLA-linked researchers into GWU. The 2015 visit led to formal agreements between GWU Medical School and Xi’an Jiaotong University Second Affiliated Hospital, including student exchanges and collaborative research. While these programs are framed as “civilian medical collaborations,” they expose U.S. institutions to PLA-influenced research networks and provide economic incentives for GWU, creating a reverse influence channel: PLA-funded projects generate revenue and prestige for GWU, while Chinese military-aligned actors gain access to U.S. academic networks and training programs.

Key Delegation Figures:

The delegation included Sidney W. Fu (known as Fu Sidong in Chinese sources)(傅四东/付四东), then holding multiple high-level roles at GWU: professor, associate director of the Genomics Medicine Center, and senior advisor to the Vice President for Health Affairs. Simultaneously, Fu served as the mentor for the International Universities Innovation Alliance (IUIA), a platform backed by CCP regime agencies and CCP united front work department’s agencies, including the Ministry of Commerce Investment Promotion Bureau, Torch High-Tech Center, Ministry of Education Science and Technology Development Center, Western Returned Scholars Association (WRSA, 欧美同学会), and Zhongguancun Management Committee. Companies like BGI (华大基因) and KingMed Diagnostics, closely linked to PLA military medical projects, were also involved.

Its leadership wasn’t symbolic. IUIA Secretary-General Sun Wansong personally reported to Xi Jinping, proving the alliance’s direct political subordination to the CCP core.

PLA Research Connections:

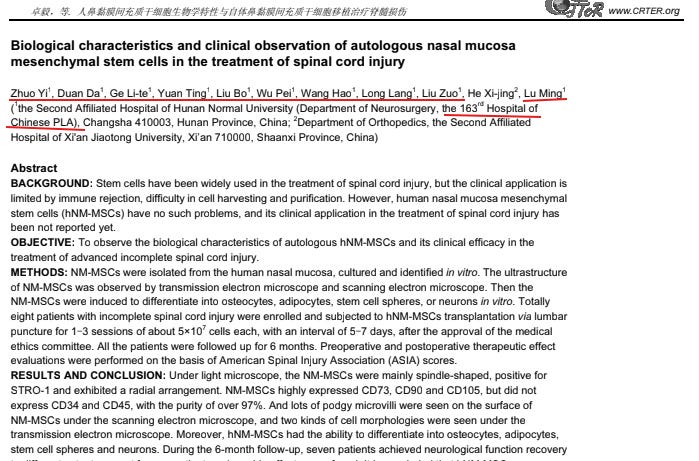

He Xijing’s research spans autologous nasal mucosa mesenchymal stem cell therapies for spinal cord injury. A 2017 publication illustrates the embedded PLA network:

Authors: Zhuo Yi¹, Duan Da¹, Ge Li-te¹, Yuan Ting¹, Liu Bo¹, Wu Pei¹, Wang Hao¹, Long Lang¹, Liu Zuo¹, He Xi-jing², Lu Ming¹

Affiliations:

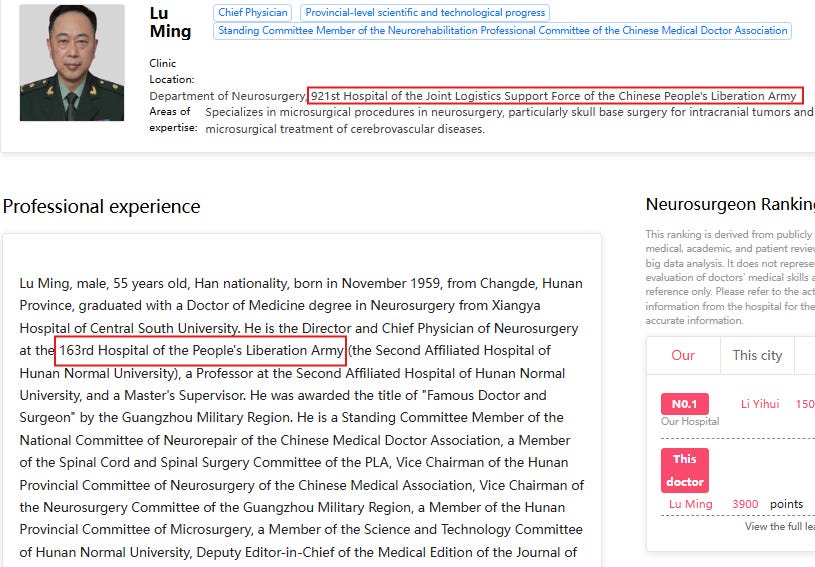

¹The Second Affiliated Hospital of Hunan Normal University (Department of Neurosurgery, the 163rd Hospital of PLA), Changsha

²XJTU Second Affiliated Hospital, Xi’an

Out of ten authors, nine are PLA personnel. He Xijing is the only researcher from XJTU 2nd Hospital. This demonstrates that PLA-affiliated researchers are integrated into ostensibly civilian collaborative projects, with the PLA exerting influence over both research outcomes and personnel placement.

IUIA and United Front Influence:

The IUIA, mentored by Fu, connects top-tier U.S. universities with Chinese innovation platforms. It has strong ties to CCP United Front entities and PLA-linked companies like BGI. Its stated mission is to accelerate research commercialization and entrepreneurship, but in practice, it creates channels for PLA-affiliated scientists and research projects to access Western institutions and resources.

GWU’s collaboration with He Xijing’s institution exemplifies the military-civil fusion model: Chinese PLA-linked medical institutions send talented young physicians to U.S. hospitals for research training, graduate programs, and joint projects. These exchanges generate both academic output and financial benefit for U.S. institutions while embedding personnel trained under PLA protocols and CCP political guidance.

A critical figure in these exchanges is Fu Sidong (傅四东), who simultaneously served as GWU faculty, genomics center deputy director, senior health affairs advisor, and mentor for IUIA. Fu has documented interactions with Qin Chuan and other PLA-aligned researchers, positioning him as a key bridge between U.S. institutions and China’s military-civilian research ecosystem. The involvement of Sidney W. Fu in both GWU leadership and the IUIA illustrates how United Front networks link PLA-related biomedical projects with international research institutions. The IUIA itself was co-founded with strong support from Chinese state organs, including the Ministry of Commerce, Ministry of Science and Technology, and organizations tied to the CCP United Front. Companies like BGI (a PLA-associated biotech leader) were also founding partners.

This network highlights a broader pattern: U.S. universities seeking collaborations with China may inadvertently participate in PLA-linked military-civil fusion initiatives, allowing military-adjacent Chinese actors to influence academic priorities, project funding, and research directions under the guise of standard biomedical cooperation.

Other collaborators, such as Lu Ming, a physician wearing PLA logistic uniforms in official photos, underscore the direct military connections of personnel participating in ostensibly civilian medical research programs. Similarly, the network includes numerous Chinese researchers in zoonotic and coronavirus studies whose affiliations with PLA institutions are well-documented.

The implications are significant: through structured academic exchanges, graduate training, and dual appointments, PLA-aligned personnel infiltrate international research networks. They gain access to sensitive biomedical technologies, establish long-term collaborations, and potentially influence research agendas and US federal government agencies under the CCP’s strategic guidance.

This network demonstrates a sophisticated blending of military objectives, civilian academic institutions, and international partnerships. The combination of formal collaborations, high-level advisorships, and strategic mentorship positions the PLA and its allies to shape global research trajectories while benefiting from the scientific infrastructure of partner nations.

For observers of U.S.-China scientific and security relations, these developments highlight a pressing need for awareness, transparency, and careful scrutiny of military-civil fusion activities that cross borders under the guise of academic collaboration.

And the risks go beyond universities. GWU’s medical faculty directly supports the U.S. Veterans Affairs (VA) system — providing research, residency programs, and patient care for American veterans. If PLA-linked collaborators gained indirect access through joint projects or data-sharing pipelines, veterans’ medical data, genomic information, or clinical trial results could become part of China’s bio-intelligence ecosystem. That would hand the CCP sensitive health insights into a demographic central to U.S. national security — the military community itself.

In other words, what began as a “friendly exchange” with a PLA hospital in Xi’an may have quietly placed America’s wounded warriors inside the scope of Beijing’s global biomedical intelligence network.

Western institutions — especially those embedded in federal or defense-linked healthcare systems — must now ask a harder question:

Are we protecting those who protected us?

If universities and medical centers fail to draw a firm line between open research and state-backed infiltration, they risk becoming unwitting participants in a project that turns care and healing into instruments of strategic exploitation.

White House Conflict of Interest?

The Xi’an–GWU connection raises deeper questions about institutional influence and financial entanglements reaching into the highest levels of U.S. government. Dr. Kevin O’Connor, President Biden’s personal physician, holds a faculty role at George Washington University, the same institution that maintained academic and institutional ties to PLA-linked hospitals and the International University Innovation Alliance (IUIA).

If entities within this network offered “research collaboration funds” or consulting payments to GWU departments or affiliated researchers — even indirectly — it could create a gray zone of influence that touches the White House Medical Unit itself. While there is no public record proving O’Connor’s personal involvement, the structural overlap between his medical chain of command and institutions engaged in CCP-linked exchanges presents a clear vulnerability.

This is not just about medical research. It’s about policy access. The White House physician has visibility into presidential health data, coordination with the Department of Defense Medical Command, and influence over national medical preparedness policy. If the CCP’s academic exchange networks have even partial access to the same institutional ecosystem, it introduces a potential channel of soft leverage that no foreign power should have.