中国的美好愿景:无核,无军队,无列宁式组织

All men are endowed by their Creator with unalienable Right of Liberty. welcome to follow @CPAJim2021 at X platform. https://x.com/CPAJim2021

军事无能的典型案例

Foreign Members of the Legal Advisory Committee of CCP united front work organ ACFROC

The Overseas Lawyers Group of the Legal Advisory Committee (LAC) of the All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese (ACFROC) was established in 2008. It was created to serve the broader objectives of the Party-state of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and to strengthen the so-called overseas rights-protection work under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

The group members are recommended by PRC embassies and consulates and are individuals with professional standing and influence within local diaspora communities. They are licensed attorneys in their respective jurisdictions or serve as legal advisers to PRC diplomatic missions.

According to official descriptions, their responsibilities include:

Safeguarding the lawful interests of PRC enterprises investing abroad.

Handling labor disputes, compensation claims, and criminal cases involving members of the PRC diaspora.

Providing legal services and free legal assistance to overseas PRC nationals and ethnic Chinese communities.

Assisting PRC diplomatic missions in activities related to opposing groups labeled by the CCP as “cults” or “separatist,” and supporting the Party-state’s reunification agenda.

Assisting PRC public security and state security authorities in protecting PRC state interests overseas and safeguarding diaspora community security.

Promoting the PRC legal system and presenting the CCP’s governance model to host countries.

Participating in return visits organized by ACFROC to provide policy feedback and recommendations on legal, political, economic, and social matters in support of Party-state objectives.

The group is formally positioned as serving the “overall interests of the Party and the state” and contributing to the protection of what the CCP defines as its core national interests.

Legal Advisory Committee (LAC)

The Legal Advisory Committee of ACFROC was established in 1982 with approval from the Party leadership of ACFROC as an internal legal advisory organ.

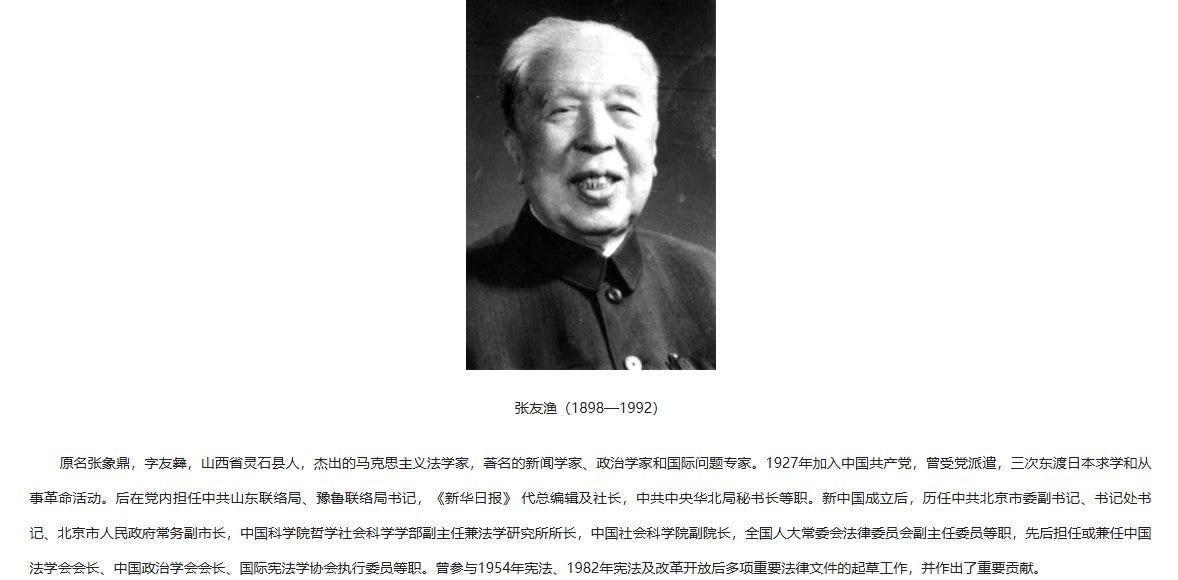

Its first director was Zhang Youyu, a Marxist legal scholar who served as legal adviser to the CCP delegation during the 1945 negotiations with the Kuomintang. He conducted united front work in culture field for CCP during WWII.

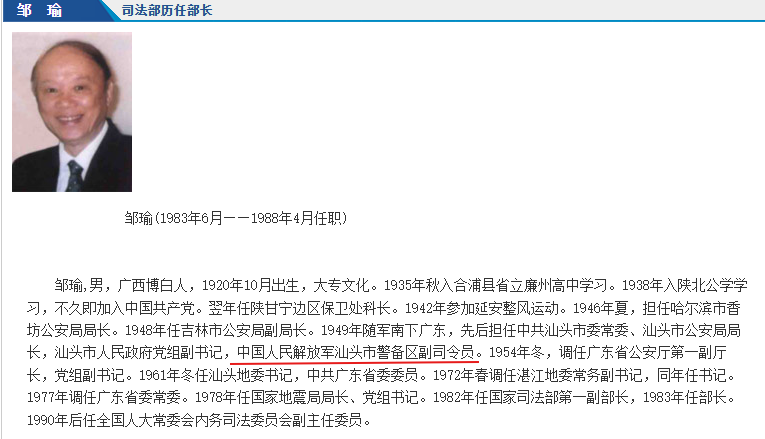

The second director was Zou Yu, former Deputy Party Secretary of Guangdong Department of Public Security, former Minister of Justice of the PRC and former deputy commander in the PLA Shantou Garrison.

The current director is Zhang Geng, former Executive Deputy Procurator-General of the Supreme People’s Procuratorate and its former Deputy Party Secretary, and former Deputy Secretary-General of the CCP Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission.

Under its charter (effective December 28, 2023), the Legal Advisory Committee (LAC) of the All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese is a legal advisory body established under the leadership of the Federation.Overseas Lawyer Members of the Legal Advisory Committee of ACFROC

The Legal Advisory Committee of the All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese (ACFROC), officially titled the Legal Advisory Committee of the All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese, is a legal advisory body established under the leadership of the All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese.

Its stated mission is to serve overseas Chinese communities in accordance with the Constitution of the PRC, the Law on the Protection of the Rights and Interests of Returned Overseas Chinese and Their Relatives, and the Charter of ACFROC. The Committee is tasked with safeguarding the lawful rights and interests of returned overseas Chinese, their relatives, and overseas Chinese nationals, both domestically and abroad.

Role of Overseas Lawyer Members

According to the Charter (revised effective December 28, 2023), overseas lawyer members are licensed attorneys of overseas Chinese origin practicing in their countries of residence who demonstrate commitment to overseas Chinese affairs. They are nominated by ACFROC, the PRC Ministry of Justice, and the All-China Lawyers Association, with the consent of PRC embassies or consulates, approved by the Committee’s leadership meeting, and formally ratified by the Party leadership or chair’s office of ACFROC.

Their core functions include:

Protecting the lawful rights and interests of overseas Chinese individuals and associations.

Providing legal advisory services to overseas Chinese communities and organizations.

Offering legal services to PRC domestic enterprises expanding abroad and safeguarding their overseas investment interests.

Contributing legal advice in support of the Belt and Road Initiative, high-level opening-up policies, and the PRC’s “dual circulation” development strategy.

Playing an active role in safeguarding what the PRC defines as core national interests, promoting peaceful reunification, and conducting people-to-people diplomacy.

Participating in exchange activities among overseas and domestic Chinese lawyers.

Assisting in legal aid efforts for economically disadvantaged returned overseas Chinese and their relatives.

Undertaking other legal tasks entrusted by ACFROC.

Organizational Structure and Oversight

The Committee operates under an appointment system, with members generally appointed before the age of 70. It includes a Chair, Executive Vice Chairs, Vice Chairs, domestic and overseas members, and a Secretary-General (who concurrently serves as head of the Rights Protection Department of ACFROC).

An Office of the Legal Advisory Committee handles daily operations and works jointly with ACFROC’s Rights Protection Department. The Committee may establish specialized subcommittees as needed.

Overseas members are required to attend the Committee’s annual meeting and may be invited to return to the PRC for visits, research activities, and official exchanges. Annual meetings include studying central policy directives, reviewing work reports, setting annual plans, and discussing revisions to the Charter and internal rules.

The Committee may organize case seminars related to overseas Chinese affairs, issue legal opinions in its institutional name, conduct research activities, and provide policy recommendations. However, individual members handling cases in their personal capacity may not represent themselves as acting on behalf of the Committee unless formally authorized.

The Committee’s operating budget is funded by ACFROC and included in its annual institutional budget.

In summary, the overseas lawyer members function within a formally structured, Party-led institutional framework. Their responsibilities combine professional legal services with policy-oriented objectives tied to overseas Chinese affairs, enterprise expansion, CCP's state interest protection, and broader PRC strategic initiatives.

Foreign Members of the Legal Advisory Committee of CCP united front work organ ACFROC by CPA Jim

Read on Substack