In today’s artificial intelligence ecosystem, few names carry as much institutional weight as Fei-Fei Li (a/k/a Li Feifei, Li Fei-Fei or any other alias).

One of the most striking yet overlooked realities is this: Fei-Fei Li, whose AI expertise is widely recognized in academia and industry, has also been formally acknowledged by People’s Liberation Army(PLA) military research programs through her collaborations with Harbin Institute of Technology.

In 2019, Stanford announced her as the first Sequoia Capital Professor, a chair directly funded by the Silicon Valley venture capital giant. This isn’t just an academic honor—it represents a strategic intersection of top-tier AI scholarship, venture capital influence, and recognition from a foreign military research apparatus.

The chain is clear:

Sequoia Capital funding → a scholar recognized by the PLA → potential structural influence on AI development and platform algorithms.

Fei-Fei Li is a member of all three elite U.S. academies—the National Academy of Engineering, the National Academy of Medicine, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She is the creator of ImageNet, widely regarded as the catalytic dataset that ignited modern deep learning. She is the first Sequoia Capital Professor of Computer Science at Stanford, the co-director of Stanford’s Human-Centered AI Institute (HAI), the seventh director of the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (SAIL), and a former Vice President at Google, where she served as Chief Scientist of AI and Machine Learning for Google Cloud.

Fei-Fei Li is not just any AI researcher—her profile reads like a map of global influence:

Special Advisor to UN Secretary-General, 2023–Present

Professor, Computer Science, Stanford University

Senior Fellow & Co-Director, Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI)

Member, Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute & Bio-X

Former Director, Stanford AI Lab (SAIL)

Member, White House National AI Research Resource Task Force, 2021–2023

Board positions in major AI non-profits and foundations

Her honors include the Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering (2025), TIME Person of the Year as one of the eight “Architects of AI” (2025), and numerous other global recognitions.

Crucially, her AI work was acknowledged by Chinese military research programs through collaborations with Harbin Institute of Technology. In 2019, she became the first Sequoia Capital Professor at Stanford, a position directly funded by Silicon Valley venture capital.

Fei-Fei Li’s relationship with the People’s Liberation Army

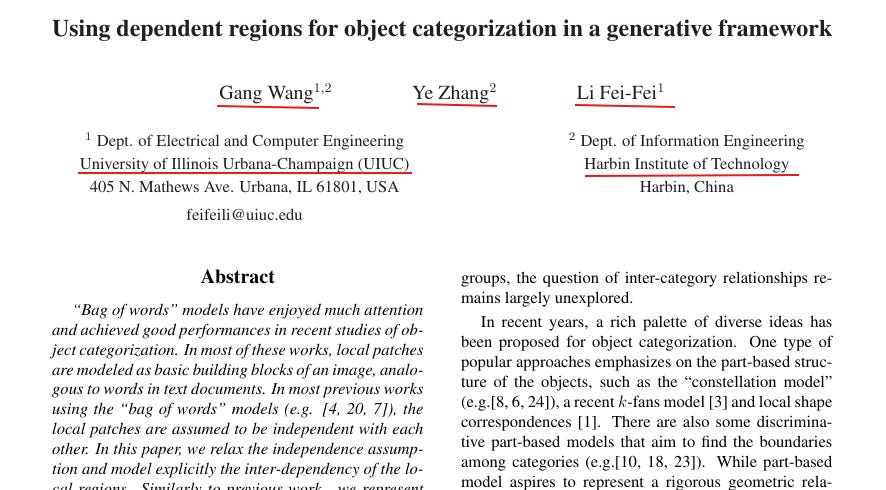

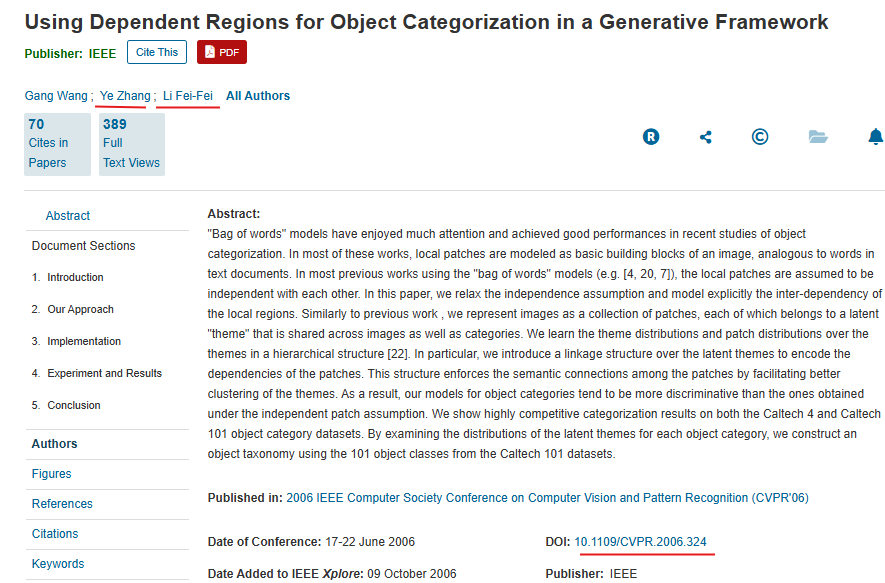

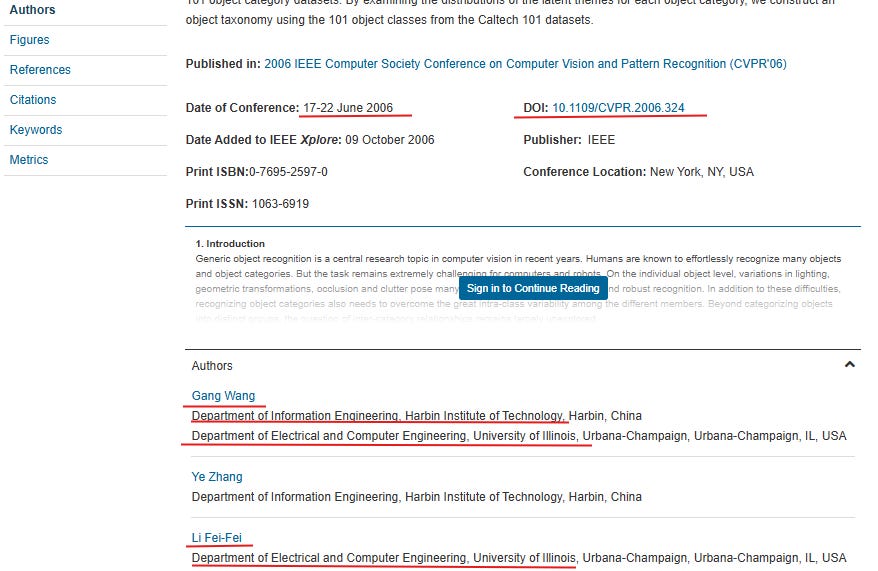

One revealing but little-discussed dimension of Li Fei-Fei’s early career is her 2006 co-authorship on “Using Dependent Regions for Object Categorization in a Generative Framework” with two researchers from Harbin Institute of Technology, including Ye Zhang(a/k/a “张晔 “, Zhang Ye, or any other alias), a professor at Harbin Institute of Technology, and Gang Wang (a/k/a “王刚”, Wang Gang, or any other alias), the former Chief Scientist of Alibaba AI Lab advertised and introduced by the introduction page of general situation of School of Electronics and Information Engineering as of 2019, Harbin Institute of Technology

Ye Zhang(a/k/a “张晔”)

Ye Zhang is not just an academic in computer vision; he is a highly experienced researcher with deep ties to Chinese Communist Party's military projects, strategic technical education, and hundreds of publications spanning image processing, signal analysis, and multi-source spatial information integration. Li’s collaboration with Zhang situates her within a formal Chinese academic and technical network at a time when she was based at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, evidencing her cross-border scientific engagement to provide help to People's Liberation Army (PLA) or military-civil fusion(MCF) indirectly. This early link demonstrates that Li’s research identity was never solely American or confined to AI and computer vision; it was transnational, cross-disciplinary, and institutionally embedded, bridging U.S. elite academia with Chinese strategic research networks. In other words, even before she became the face of AI vision research in the U.S., her career trajectory already leveraged institutional access, technical breadth, and international networks—a continuity of elite positioning that has been largely invisible in public narratives.

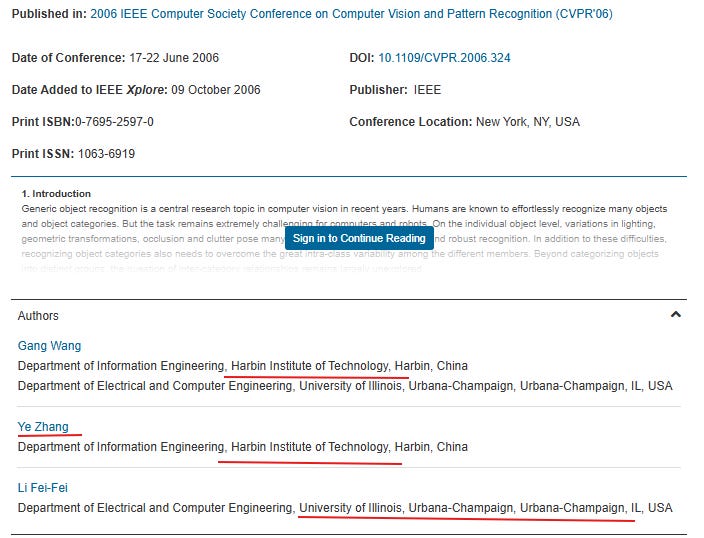

In 2005, Ye Zhang co-authored a paper “ANOMALY DETECTION ALGORITHM OF HYPERSPECTRAL IMAGES BASED ON SPECTRAL ANALYSES(基于光谱解译的高光谱图像奇异检测算法)“ with Gu Yanfeng(谷延锋), who holds multiple positions directly tied to national defense research. Gu is a professor and PhD supervisor at HIT, director of the Heilongjiang Provincial Key Laboratory for Integrated Space–Air–Ground Intelligent Remote Sensing, and Associate Editor of IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing. He has led multiple national defense priority projects and was awarded the Second Class Science and Technology Progress Award of the People’s Liberation Army. The paper explicitly describes Gu’s research as focusing on hyperspectral imaging and machine learning methods applied to nuclear-related sensing and analysis. This indicates that Ye Zhang’s collaborative research environment was embedded in a military-oriented, nuclear-adjacent technical ecosystem, where machine learning, computer vision, and remote sensing research were directly linked to strategic military programs. The paper itself, publicly accessible here, lists Gu Yanfeng’s HIT affiliation, demonstrating that this research was institutionally and operationally connected to military projects, rather than being a purely civilian or academic endeavor.

Gang Wang (a/k/a “王刚”)

Gang Wang (a/k/a “王刚”, Wang Gang, or any other alias), one of the co-authors of the 2006 CVPR paper “Using Dependent Regions for Object Categorization in a Generative Framework,” has a background that is particularly notable in the context of technology transfer and military-civil fusion. He received his undergraduate education at Harbin Institute of Technology (HIT), an institution long embedded in PRC’s aerospace and defense research system, especially in radar, communications, and information engineering. During his doctoral studies at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC), Wang Gang studied under Li Fei-Fei, alongside other leading figures in computer vision, bridging HIT’s information-engineering tradition with one of the core academic hubs of U.S. computer vision research. After an academic career that included a tenured professorship at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Wang later transitioned into industry, becoming Chief Scientist of Alibaba’s Artificial Intelligence Lab and subsequently a senior executive overseeing autonomous driving research. Chinese state-affiliated technology media have explicitly highlighted both his mentorship under Li Fei-Fei and the 2006 CVPR publication itself, underscoring its role in his career trajectory. Taken together, Wang Gang’s profile illustrates a continuous pathway linking defense-oriented engineering education, elite U.S.-based AI research training, and leadership roles within a major Chinese platform company—an intersection increasingly relevant to U.S. assessments of advanced AI capabilities and corporate exposure to military-linked research ecosystems.

Importantly, the authorship information of the 2006 CVPR paper makes this connection explicit rather than inferential. In the official IEEE record, Wang Gang is listed with dual institutional affiliations: the Department of Information Engineering, Harbin Institute of Technology (HIT), China, and the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC), USA, where Li Fei-Fei was then a faculty member. This dual affiliation confirms that the collaboration was not a retrospective or purely personal connection, but an active, formally recognized research linkage spanning a defense-oriented Chinese engineering institution and a leading U.S. AI research environment. Such dual-institution authorship reflects a structured academic bridge, one that predates later industry roles and demonstrates how personnel trained within China’s national defense–linked universities were simultaneously embedded in core U.S. computer vision research during the formative years of modern AI.

Even though Li Fei-Fei’s co-authored paper with researchers from Harbin Institute of Technology (HIT) was published in 2006—well before HIT was later placed under U.S. Department of Defense restrictions—it is not credible to argue that such collaboration was entirely unrelated to the Chinese Communist Party’s military-civil fusion strategy or to the operational capabilities of the People’s Liberation Army. HIT has, since the Cold War era, functioned as a core node within the CCP’s defense science and aerospace system, with longstanding institutional mandates in radar, communications, electronic warfare, information countermeasures, and space systems. These roles were firmly established decades before any U.S. sanctions regime existed. Consequently, the absence of formal U.S. designations at the time does not negate the structural reality that research outputs—particularly in computer vision, signal processing, and information engineering—were developed within, and potentially absorbed by, an ecosystem explicitly designed to serve national defense and military modernization objectives. In this context, temporal arguments based on “pre-sanctions” collaboration are analytically weak and strategically misleading.

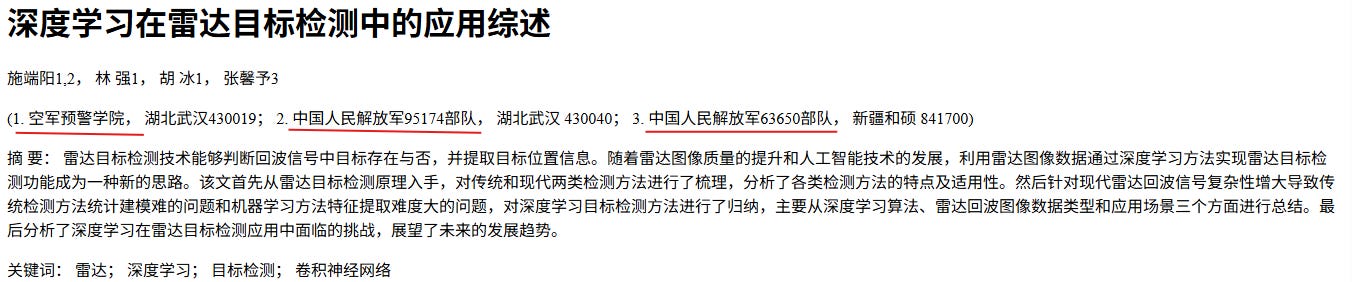

PLA's Mentioning of Fei-Fei Li’s Contribution to military radar target detection

Notably, Li Fei-Fei’s contributions to deep learning are explicitly recognized in PLA research publications. A 2022 review paper on radar target detection lists the following affiliations:

Air Force Early Warning Academy of PLA (中国人民解放军空军预警学院), Wuhan, Hubei

PLA Unit 95174 (中国人民解放军95174部队), Wuhan, Hubei

PLA Unit 63650 (中国人民解放军63650部队), Hoxud, Xinjiang

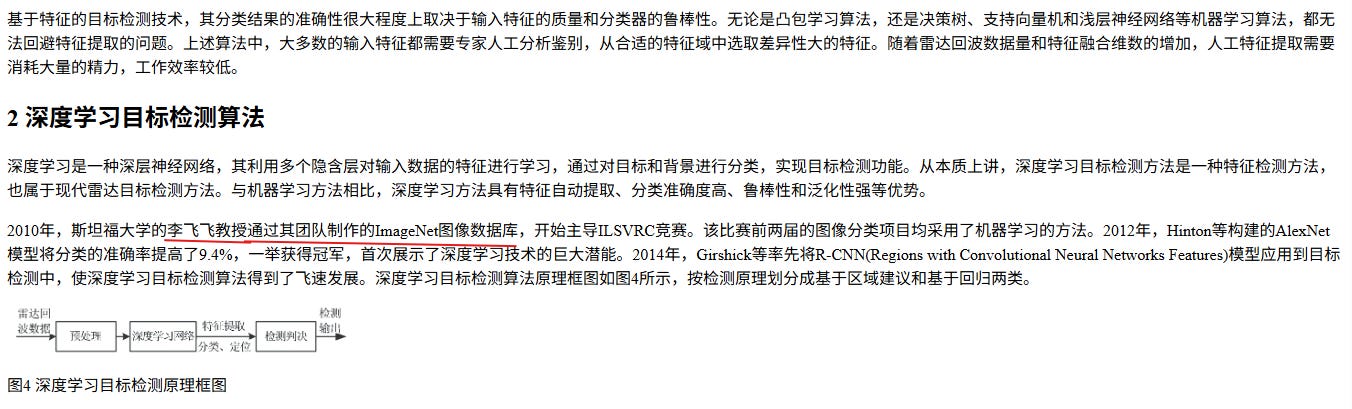

The paper explicitly cites Li’s 2010 creation of the ImageNet database and her dominating of the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge competitions, highlighting her team’s foundational role in enabling deep learning methods to be applied to radar image analysis. This demonstrates that Li’s work is not only a landmark in academic computer vision but has also been influential in military applications, such as modern radar target detection, underscoring the global and cross-domain reach of her research.

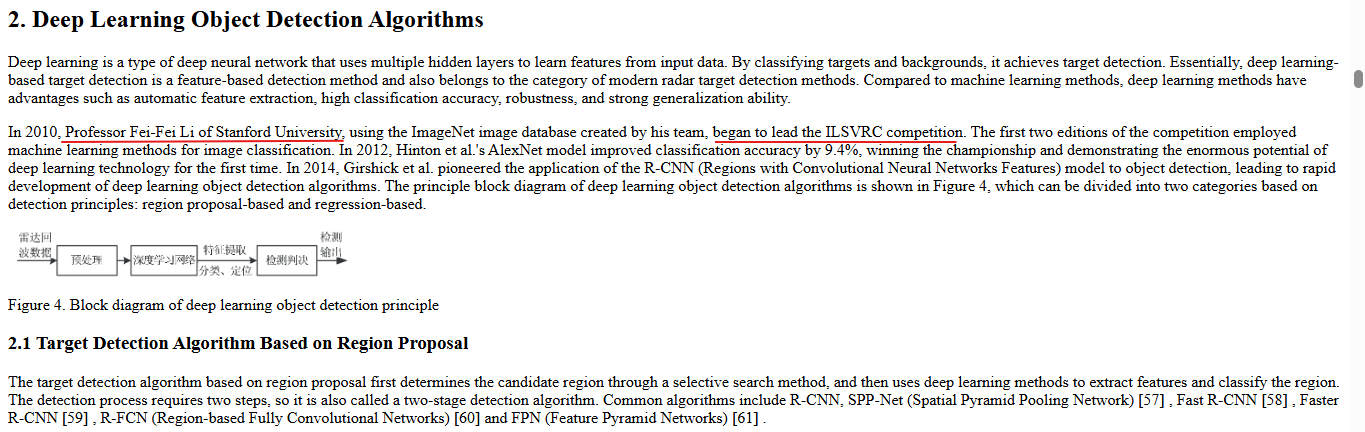

The ILSVRC Legacy: From ImageNet to Deep Learning Breakthroughs

The ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC), launched in 2010, was a landmark competition in computer vision, built on the ImageNet dataset created by Li Fei-Fei’s team at Stanford. ILSVRC challenged algorithms to perform large-scale image classification, object localization, and object detection across thousands of categories using millions of labeled images. In 2012, the competition marked a turning point. AlexNet, developed by Alex Krizhevsky under the supervision of Geoffrey Hinton, leveraged deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to dramatically improve classification accuracy, outperforming traditional machine learning methods by a wide margin. This success showcased the potential of deep learning for visual recognition at scale. Building on this momentum, researchers soon extended deep learning beyond classification. In 2014, R-CNN (Regions with Convolutional Neural Networks Features), developed by Ross Girshick and colleagues at UC Berkeley, enabled algorithms to detect and localize multiple objects within a single image. This bridged the gap between recognizing what is in an image and understanding where each object resides—a crucial step for applications ranging from autonomous vehicles to robotics and surveillance.

Fei-Fei Li’s Relationship with CCP’s Tianjin University

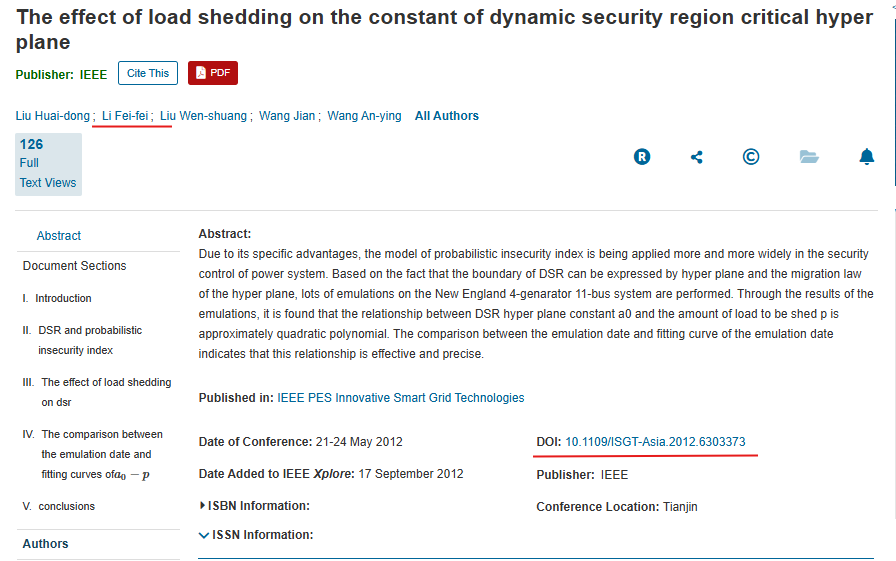

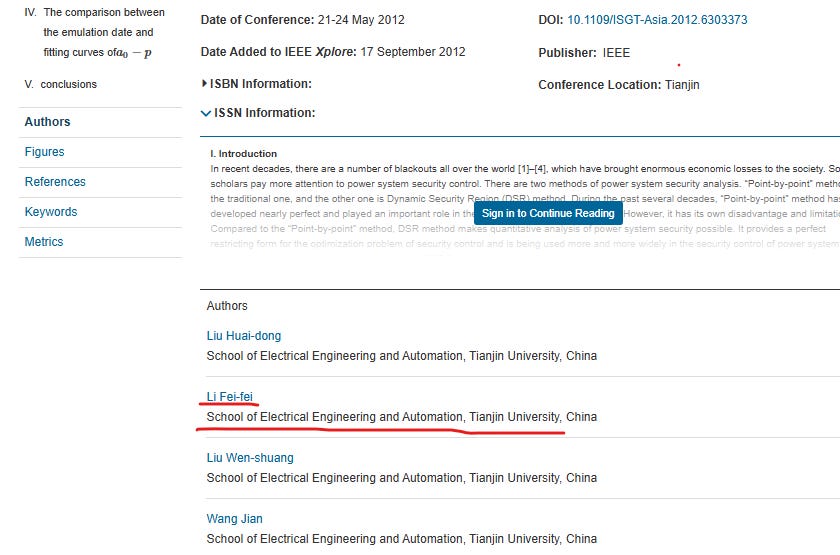

What emerges from digging into her publication record is a fact rarely, if ever, mentioned in public biographies or media profiles: Li Fei-Fei, widely portrayed as an American AI visionary and computer vision expert, also holds formal academic ties to Tianjin University. Her name appears on a 2012 IEEE paper, “The effect of load shedding on the constant of dynamic security region critical hyper plane“, in the field of electrical engineering and smart grid technologies, alongside Chinese co-authors. e Liu Huai-dong (刘怀东), a co-author, is an Associate Professor and master’s supervisor at the School of Electrical Automation and Information Engineering, Tianjin University. He has spent over three decades in the field of electrical engineering, specializing in power system safety and stability, electricity markets, renewable energy integration, and smart energy systems. He earned both his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in Electric Power Systems and Automation from Tsinghua University (1979–1987), one of Chinese Communist Party’s premier technical institutions. Since 1987, he has held teaching and research positions at Tianjin University, mentoring graduate students and leading projects in power system modeling and control.

Fei-Fei Li’s Relationship with CCP Party Committee of Alibaba Group

In October 2018, Stanford University officially renamed its neuroscience institute the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute in recognition of a major philanthropic gift from Clara Wu Tsai and Joseph Tsai. The gift was claimed to be aimed at accelerating interdisciplinary research on human brain health and disease, including projects on depression, anxiety, and Alzheimer’s disease. Clara Wu Tsai, a Stanford alumna, has held advisory roles across multiple Stanford research initiatives, while Joseph Tsai is co-founder and executive vice chairman of Alibaba and one of the company’s two “permanent partners.” This renaming, combined with Li Fei-Fei’s leadership roles as co-director of the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI) and member of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, illustrates a public, verifiable institutional overlap: AI research leadership, major Stanford neuroscience funding, and Alibaba executive involvement.

Stanford’s neuroscience connection to Alibaba’s inner circle sharpens the institutional picture. Joseph Tsai (蔡崇信)—longtime Alibaba executive and one of the company’s two “permanent partners”—and his wife, Clara Wu Tsai (吴明华), have been major donors to Stanford; their gift prompted the renaming of Stanford’s neuroscience institute as the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Chinese media profiles of the Tsai family explicitly link Joseph Tsai’s central role at Alibaba with the couple’s philanthropic activities. Fei-Fei Li, for her part, serves as co-director of Stanford’s Human-Centered AI Institute (HAI) and is listed as a member of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute.

The influence of the Alibaba Group Party Committee may extend to Stanford connections through the Tsai couple. Joseph Tsai, co-founder and permanent partner of Alibaba, and Clara Wu Tsai, a major donor to Stanford, jointly funded the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute in 2018. 2023 news shows the Alibaba Group’s Chinese Communist Party Committee actively aligning company leadership with CCP directives on tech innovation, platform governance, and high-level science projects. Combined with Li Fei-Fei’s roles as co-director of Stanford HAI and member of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, this highlights a concrete institutional link where Chinese corporate-party-aligned interests intersect with U.S. AI and neuroscience leadership.

The directives from the Alibaba Party Committee, reinforced by the Zhejiang provincial secretary Yi Lianhong (易炼红), suggest that the Party’s influence on network governance within Alibaba has long been present, though not fully exercised. By emphasizing the need to “better leverage the Party Committee’s role in network governance” and strengthen Internet enterprise Party-building, the authorities signal an expectation for deeper oversight of corporate decision-making, platform management, and technological initiatives. For Fei-Fei Li, who collaborates with Alibaba-linked projects, this implies that her work in AI, platform development, and related research could be subject to increasing guidance or influence from Party structures, shaping both strategic priorities and operational approaches.

The Zhejiang provincial secretary’s engagement with Alibaba, framed around implementing Xi Jinping’s key speeches and directives on private enterprise, signals a channel through which central Party guidance reaches the company. By emphasizing alignment with national strategies for technological innovation, platform governance, and high-quality corporate development, these directives create a framework in which Alibaba’s initiatives—including AI research and platform operations connected to Fei-Fei Li—are expected to reflect Party priorities. This suggests that Fei-Fei Li’s work, whether in collaboration with Alibaba or on projects influencing digital platforms, may be shaped by the broader political and strategic objectives set forth by Xi and communicated through provincial and corporate Party leadership.

Fei-Fei Li’s Censorship Emperor role at Twitter

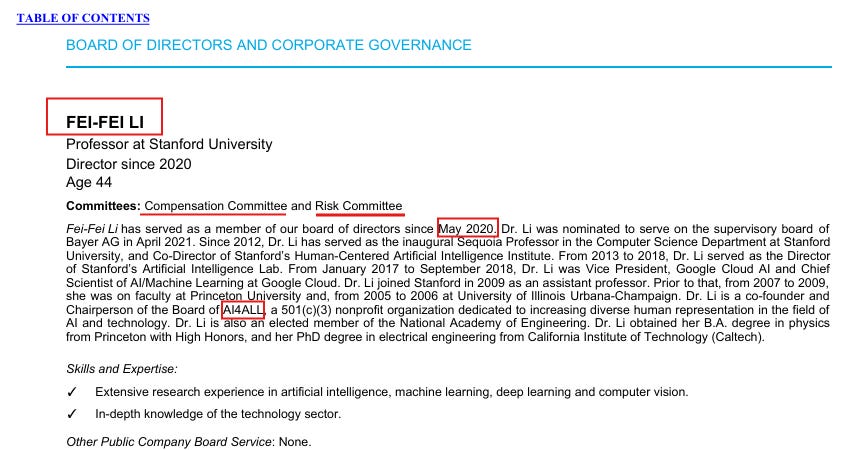

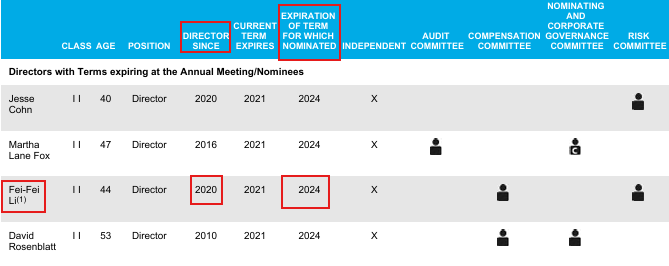

Fei-Fei Li’s board roles at Twitter reveal a concentration of influence few outsiders can see. By simultaneously serving on the Risk Committee and the Compensation Committee, she occupied a structurally incompatible position: the former empowers her to define risk policies and evaluate whether management adheres to them, while the latter gives her leverage to reward or punish executives based on that compliance.

This dual authority creates a direct operational lever, allowing a single director to enforce her risk preferences across the company. Layered on top of that is her unique linguistic and cultural expertise—her fluency in Chinese and deep understanding of Chinese culture give her disproportionate sway over decisions involving Chinese-language content or China-related operations. Management and fellow board members, lacking equivalent expertise, are likely to defer to her judgment. The result is a board structure that is nominally collective but, in practice, enables a single director to define risk standards, monitor execution, and pressure management, effectively concentrating decision-making power in one individual—a textbook example of how committee design and personal expertise can intersect to produce outsized influence.

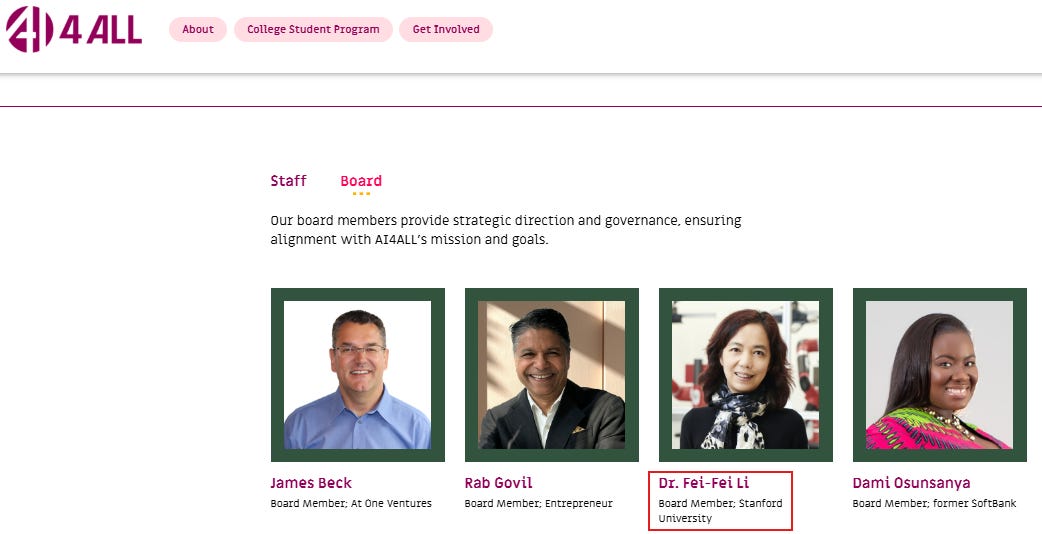

Fei-Fei Li’s influence extends beyond Twitter into the nonprofit sphere. As a founding board member of AI4ALL, she sits alongside a network of top-tier academics, tech executives, and investors, including Stanford and Princeton professors, former SoftBank leadership, and prominent AI entrepreneurs. Her combination of academic authority, industry experience, and cultural-linguistic expertise gives her disproportionate weight in strategic and operational discussions, allowing her to shape not only talent pipelines and educational initiatives, but also indirectly affect corporate decision-making. When considered alongside her dual roles on Twitter’s Risk and Compensation Committees, this positions Li as a multi-dimensional lever of power, capable of influencing both management behavior and the broader AI ecosystem

Fei-Fei Li's Relationship with X Platform of Elon Musk after leaving Twitter (从推特离职后的李飞飞与马斯克的X平台的关系)

In this context, the title “Sequoia Capital Professor” held by Fei-Fei Li or Li Fei-Fei refers not to an academic rank created by Stanford itself, but to an endowed chair funded or established by Sequoia Capital, one of the most influential venture capital firms. According to Stanford’s 2019 announcement, Li Fei-Fei became the first faculty member to hold this endowed professorship, while simultaneously serving as co-director of Stanford’s Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI) institute. Endowed chairs of this type are typically established through long-term financial commitments from private donors, granting the holder enhanced institutional visibility, discretionary research resources, and agenda-setting influence. In practice, a Sequoia-funded professorship situates its recipient at the intersection of academic research, venture capital priorities, and technology commercialization, especially in fields—such as artificial intelligence—where research directions can directly shape market formation, startup ecosystems, and downstream industrial adoption. The designation therefore signals not only scholarly distinction, but also a formalized structural linkage between Stanford’s AI research leadership and a major global investment firm.

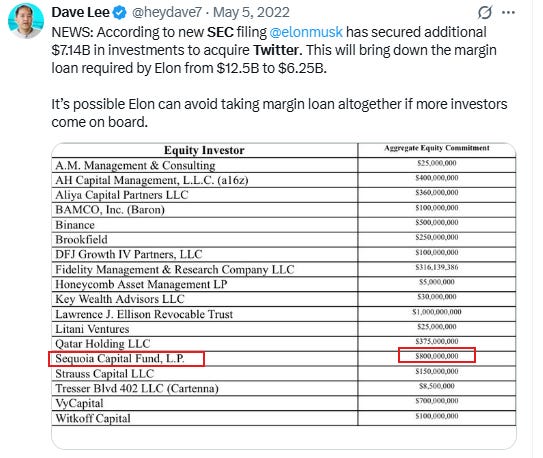

Sequoia Capital was a direct equity participant in Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter in 2022. According to disclosures made after the transaction closed, Sequoia committed approximately $800 million as part of the investor consortium backing Musk’s buyout. This placed Sequoia among the largest non-Musk financial stakeholders in the deal, alongside entities such as the Qatar Investment Authority and major private investors from the U.S. and abroad.

Sequoia’s financial participation at that scale confers strategic proximity rather than passive distance. The firm has a long history of backing platform-defining technology companies and has invested across Musk-adjacent ecosystems, including firms tied to artificial intelligence, data infrastructure, and consumer platforms. Its role in the Twitter acquisition therefore situates Sequoia not merely as a venture investor, but as a capital actor embedded in the ownership structure of a major global information platform during a period of intense political, regulatory, and technological scrutiny.

When viewed alongside Sequoia’s institutional ties to Stanford—most notably its funding of an endowed professorship held by Li Fei-Fei—the Twitter investment highlights a recurring pattern: the same venture capital firm simultaneously occupying influential positions across academic AI research, startup ecosystems, and high-impact social media infrastructure. This convergence does not imply coordinated intent, but it does underscore how agenda-setting power in AI, platform governance, and information flow can become structurally concentrated within a small set of private financial institutions.

Public reporting surrounding the Twitter acquisition further reinforce this structural linkage. A substantial portion of Elon Musk’s equity contribution to the deal was financed through sales of Tesla shares, explicitly tying the ownership structure of Twitter (now X) to the valuation, liquidity, and market dependencies of Tesla. Given Tesla’s significant operational and revenue exposure to China, this financing mechanism establishes a direct financial conduit between a global social media platform and a company deeply embedded in the PRC market. The relevance of this link does not hinge on intent or editorial decisions, but on capital sourcing: when platform ownership is partially funded by assets whose value depends on regulatory and market conditions in China, those conditions become structurally relevant to platform governance outcomes.

The Financial Times’ reporting that Sequoia committed to back Elon Musk’s xAI tightens the capital thread in this story. Sequoia’s repeated investments—into Twitter/X’s buyout, Musk’s xAI, and historically into platform-scale ventures—mean the same financial actor occupies persistent positions across academic funding, platform ownership, and cutting-edge AI startups. That recurrence makes the relationship a structural variable: it raises legitimate questions about how concentrated capital alignments shape long-term incentive structures across research agendas, platform governance, and model development—regardless of any single actor’s intent.

Fei-Fei Li’s Relationship with Google

Fei-Fei Li’s roles at Stanford — co-director of HAI, member of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, and leader of AI4ALL — combined with her close collaboration with major tech players like Google, AWS, IBM, and Wells Fargo, raise a critical question: to what extent is her work purely academic, and to what extent is it strategically shaping the U.S. tech ecosystem? When a university platform is leveraged to influence corporate AI development, mentorship pipelines, and policy recommendations, it blurs the line between independent research and industry-aligned coordination. Is Stanford serving knowledge and innovation, or acting as a hub where global tech, capital, and strategic influence intersect under the guise of academia? The transparency of intent here demands scrutiny.

Stanford’s 2019–2020 HAI Annual Report highlights AI4ALL, a nonprofit co-sponsored by HAI, dedicated to increasing diversity and inclusion in AI. The program creates pipelines for underrepresented talent via U.S. and Canada high school mentorships and summer internships, exposing students early to AI for social good. In FY20, corporate giants including Google, Wells Fargo, AWS, and IBM joined as Founding Corporate Members. These collaborations span research on the future of work, equity, and healthcare AI applications. This demonstrates that Li Fei-Fei’s HAI leadership not only guides AI research but also coordinates with major tech and finance companies, providing early access to talent pipelines and potentially shaping AI deployment and governance.

🔥 Core Insight: HAI → Industry Influence → AI Policy & Platform Guidance

Stanford’s Human-Centered AI Institute (HAI), co-directed by Fei-Fei Li, explicitly links academic research, industry partners, and policy influence. The 2024 annual report states:

“Over the past year, HAI broadened its reach with industry partners while deepening existing collaborations, working within an expanding corporate ecosystem to guide decision makers and ensure that AI technologies are deployed with a strong focus on human-centered approaches.”

Notably, Google is listed as a key partner, meaning HAI—under Li’s leadership—serves as a hub connecting academic authority, corporate AI strategy, and human-centered policy guidance.

Combined with earlier points—Sequoia Capital funding → PLA-recognized collaborations → AI/platform influence—this forms a multi-dimensional network showing how scholarly expertise, venture capital, and major tech corporations intersect, potentially shaping both AI development and algorithmic governance at scale.

Origins: From Beijing to Chengdu of Communist China

Fei-Fei Li was born in Beijing in 1976, with her grandparents’ family rooted there. However, she grew up primarily in Chengdu, Sichuan, following her parents’ work relocation. Li attended Chengdu No. 7 High School, one of Sichuan’s top key schools—already signaling early access to educational filtering mechanisms that mattered deeply in China’s system.

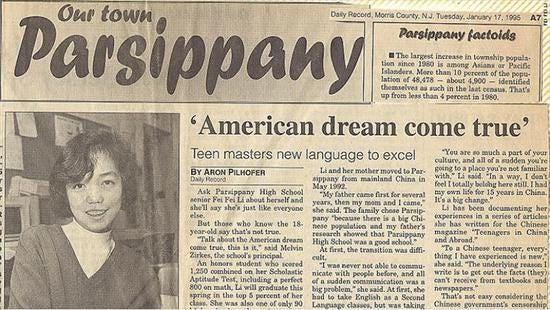

In 1992, at age 16, Fei-Fei Li emigrated to the United States with her parents, settling in New Jersey. By 1995, she scored 1250 on the SAT and was admitted to Princeton University as a physics major with a full scholarship—an achievement highlighted by local newspapers, which praised her performance relative to native-born students. A local New Jersey newspaper reported on her admission, highlighting that her performance exceeded that of many local students. This episode is often framed as proof of extraordinary individual brilliance overcoming adversity. It is that—but it is also proof of something else: a system that reliably identifies, funnels, and amplifies already elite academic talent once it enters Western institutions.

This was the decisive pivot: permanent insertion into America’s elite academic pipeline.

What Princeton Officially Said in 1999

In March 1999, Princeton University published an official announcement about Fei-Fei Li ’99 that is rarely cited today—but is extraordinarily revealing.

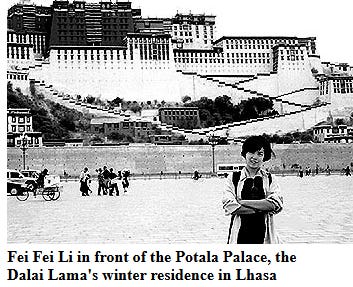

According to Princeton’s own account, Li was awarded the Martin A. Dale ’53 Fellowship, a competitive post-graduation grant of $20,000 designed to fund an independent year-long project. She titled her proposal “Exploring Tibetan Medicine, An Untapped Resource,” and planned to travel to Tibet to study its traditional medical system.

The announcement explicitly notes that Li was able to travel to Tibet freely on her Chinese passport—a detail that carries significant political and administrative implications given the sensitivity of the region in the late 1990s.

While there, Princeton reported, Li met with professors and physicians at the Tibetan Medical Institute and with a “Living Buddha,” Suo Lang Dun Zhu, described as a leading figure in Tibetan medicine. The university framed her work as a bridge between Western science and Asian cultural traditions, emphasizing openness to non-Western epistemologies alongside scientific rigor.

The same announcement details a remarkably broad technical background already in place before Li entered graduate school. Though officially a physics major, she had devoted most of her undergraduate time to research that combined neuroscience, biology, computer science, electrical engineering, and applied mathematics. Her projects included studies on auditory and visual signal processing in the brain, conducted in part at UC Berkeley’s Department of Cellular and Molecular Biology, and a coauthored paper submitted to Nature Neuroscience. This intense focus on cross-disciplinary research provided her with the technical foundation, American scientific materials and analytical skills, which PLA troops stationed in Tibet may need, that would later support her yearlong research project in Tibet, where she studied traditional Tibetan medicine under a Martin A. Dale Fellowship, combining her scientific training with immersive field experience.

Fei-Fei Li’s technical and engineering foundation appears to have deep roots both academically and familially. During her undergraduate years at Princeton, she had already begun research involving electrical engineering, a field in which her father, Shun Li, had professional experience prior to 1992 as an engineer in the computer department of a chemical plant in Chengdu. Her departure to the United States in early 1992 at age 16 would likely have required formal approval by the relevant Chinese government authorities managing overseas study, potentially coordinated through offices in Chengdu. By 1998, Fei-Fei Li had returned to China, and any travel to Tibet for her Martin A. Dale Fellowship project would have plausibly involved transit through Chengdu, where she had familial ties and potential logistical support. Taken together, these factors suggest that her undergraduate research trajectory, family technical background, and high-altitude fieldwork were conducted in a context in which CCP government oversight or facilitation mechanisms plausibly played a role.

Equally notable was Li’s role in organizing an international conference at Princeton in 1997 to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Nanking Massacre. The event brought together scholars from around the world and resulted in a forthcoming edited volume. Li told the fellowship committee that the goal was to help “heal past scars” and contribute to a more peaceful future—language that situates her scientific identity firmly within a broader framework of historical memory and humanitarian narrative-building.

Given the physiological challenges of the high-altitude environment, such activities would have required professional high-altitude training and logistical support—resources that, in China, can only be provided or approved by government-recognized institutions. This underscores that her presence in Tibet was organized and formally facilitated, rather than spontaneous or purely individual.

Fei-Fei Li family’s deep relationship with Beijing

Fei-Fei Li’s formative environment was anything but incidental. Her grandparents’ home in Beijing, the political and military heart of the People’s Republic of China, placed her family at the nexus of state power, the People’s Liberation Army(PLA) and defense industry influence. Born in Beijing and raised with close familial ties to technically skilled relatives—her father an engineer, her uncle practicing traditional acupuncture—Li’s early life combined both the elite scientific and culturally embedded networks of the PRC. Later, as a Princeton undergraduate, she was able to travel freely to Tibet for research, engaging with traditional medicine and cultural authorities in ways inaccessible to ordinary students. Taken together, these facts suggest that from birth, Li occupied a position uniquely suited to navigate sensitive political landscapes, integrate diverse knowledge systems, and function as a cross-cultural, strategically positioned talent—far from the accidental success story often portrayed in public narratives.

Elite Academies, ImageNet—and the System She Came Through

Fei-Fei Li(李飞飞) is often portrayed as a self-made immigrant success story in China: a brilliant teenager, cultural outsider, and future AI pioneer who rose purely through talent and perseverance. That narrative is comforting—and incomplete.

To understand her real positioning in the global AI power structure, one must examine not only her résumé, but also the institutional system that governed her departure from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and shaped the obligations, expectations, and political framing of overseas students.

The Legal Reality of “Going Abroad”

In December 1986, the PRC State Education Commission issued the “Provisional Regulations on the Work of Personnel Studying Abroad”, pursuant to a joint directive from the CCP Central Committee and the State Council.

This document matters because it explicitly demolishes the Western assumption that Chinese students leaving in the 1980s–1990s were acting as independent individuals detached from state oversight.

Key principles included:

All Chinese citizens studying abroad—publicly funded or self-funded—were part of a unified national personnel system.

Overseas students were required to:

Obey PRC laws and regulations

Maintain contact with PRC embassies and consulates

Accept political education, including patriotism, collectivism, and socialist moral instruction

Embassies were formally tasked with:

Maintaining regular contact with students

Conducting ideological guidance

Encouraging loyalty and future service to “socialist modernization”

Even self-funded students were:

Treated politically “the same as state-sponsored students”

Encouraged to return and serve national development

Eligible for state-arranged job placement upon return

This was not optional. It was the law of the People’s Republic of China (PRC),controlled by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Fei-Fei Li’s Departure in Context

Fei-Fei Li left China in 1992, at age 16—squarely within the period when these regulations were actively enforced.

Her family background fits the profile precisely:

Father: Shun Li (李舜), electrical engineer in a chemical factory computer department. Her father, Shun Li, worked in the computer department of a Chengdu chemical factory and was trained as an electrical engineer.

Mother: Ying Kuang (邝颖), teacher turned office cadre.Her mother, Ying Kuang, initially worked as a high school teacher before later becoming an office administrator.

Residence: Chengdu, not a marginal or rural environment

Education: key provincial high school

This was not a household disconnected from technology, education, or institutional privilege. It was a technically literate, professionally embedded family during a period when such positioning mattered enormously.

Li attended Chengdu No. 7 High School, one of Sichuan Province’s key elite high schools, reserved for top-performing students. Admission alone signals academic filtering long before any Western opportunity appeared.

This was the technocratic class the CCP explicitly targeted for overseas training.

Whether her departure was formally labeled “self-funded” or not is irrelevant under PRC law. The 1986 regulations are explicit: self-funded study abroad was a state-supported channel for talent cultivation, subject to embassy contact, ideological guidance, and future expectations of service.

In other words, there was no such thing as a politically neutral Chinese overseas student in that system.

Embassies, Contact, and Access

Under the regulations:

Students from the PRC were required to register with PRC embassies and consulates

Embassies were required to actively maintain contact

Embassies were instructed to:

Assist students materially

Protect their interests

Conduct ideological education

This framework explains a critical fact often ignored in Western profiles of Fei-Fei Li:

She traveled freely in Tibet on a Chinese passport, conducted research, and met high-ranking religious and medical figures—access that is impossible without state approval.

Her Dale Fellowship project—studying Tibetan medicine, meeting a Living Buddha, and positioning herself as a cultural–scientific bridge—did not occur in a vacuum. It occurred within a sovereignty and permissions regime tightly controlled by the CCP.

Education Before 1992: What Fei-Fei Li Was Actually Taught in China

Before leaving for the United States in 1992, Fei-Fei Li spent her entire childhood and early adolescence inside the People’s Republic of China’s state education system. Assuming she entered primary school around age six, this places her schooling squarely between 1982 and 1992 in Chengdu, Sichuan. Li attended Chengdu No. 7 High School, one of Sichuan’s top key schools—already signaling early access to educational filtering mechanisms that mattered deeply in China’s system.

During this period, Chinese primary and secondary education was explicitly designed to serve a political function: the cultivation of “socialist builders and successors” under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party. Civic education was not centered on individual rights, constitutionalism, or political pluralism. Concepts such as freedom of speech, multiparty democracy, separation of powers, or opposition to communism were not part of the curriculum and were treated as ideologically hostile ideas.

From the earliest grades, students were required to study “moral and ideological education”, emphasizing collectivism, obedience to authority, patriotism defined through loyalty to the socialist state, and the legitimacy of one-party rule. Political content was not confined to a single subject: it was embedded in language textbooks, history lessons, and school rituals. Students memorized revolutionary narratives, model-hero stories, and slogans affirming the Party’s role as the savior and organizer of the nation. Participation in state youth organizations, such as the Young Pioneers, reinforced early political identity formation through symbols, oaths, and hierarchical structures.

The timing matters. Fei-Fei Li’s middle-school years coincided with the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown and its aftermath, after which ideological control in schools was tightened nationwide. In the early 1990s, particularly in inland provinces such as Sichuan, educational authorities explicitly warned against “bourgeois liberalization,” and schools were required to strengthen political discipline and ideological conformity. This environment did not encourage open political debate; it trained students to treat politics as sensitive terrain best navigated through caution and silence.

It establishs a basic fact often obscured in Western narratives: her pre-1992 education did not cultivate liberal democratic values, nor was it intended to.

ImageNet and the Politics of Vision

ImageNet made Fei-Fei Li famous, but it also granted her something more consequential than academic recognition: agenda-setting power.

Datasets decide:

What counts as an object

What counts as a category

What is visible, and what is erased

The creator of a global dataset is not just a scientist. She is a curator of reality for machines.

From there, her ascent into:

Stanford’s top AI roles

Google Cloud’s AI leadership

The U.S. National Academies

Global AI ethics forums

was not merely technical success—it was institutional consolidation.

“Human-Centered AI” and Selective Silence

Today, Fei-Fei Li speaks fluently about:

Ethics

Responsibility

Human-centered AI

What she does not speak clearly about is:

The CCP’s role in shaping overseas talent systems

State control over academic mobility

The political obligations imposed on Chinese nationals abroad

The moral asymmetry between Western openness and CCP governance

This silence is not accidental. It is structural.

She embodies a specific archetype:

The globally celebrated technocrat who defines ethical language while avoiding confrontation with the political system that enabled her early mobility and continuing access.

Equally important to what Fei-Fei Li has said is what she has consistently not addressed in public.

To date, she has not publicly confronted the documented impact of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) censorship and information suppression in late 2019 and early 2020, when early warnings about human-to-human transmission of COVID-19 were delayed or silenced. Nor has she publicly examined how those censorship mechanisms—many of them increasingly automated—affected global pandemic response during its most critical window.

Despite formal training that spans neuroscience and biological systems, she has not publicly addressed the CCP regime’s obstruction of independent international investigations into the origins of COVID-19, nor has she used her institutional standing to press for transparency regarding laboratory governance, data access, or biosafety accountability. She has also not publicly engaged with materials released or discussed by the U.S. Congress concerning the relationship between the Wuhan Institute of Virology and the People’s Liberation Army, even as those materials became central to COVID-19 truths debates.

More broadly, she has not publicly mentioned the role of AI-enabled infrastructure in the CCP’s domestic control system—specifically, the integration of the Great Firewall, mass surveillance, facial recognition, and algorithmic content moderation into a comprehensive censorship and population-monitoring regime. This omission is notable given her prominence as a leading voice on “human-centered AI” and ethical AI deployment.

These silences, taken individually, prove nothing. Taken together, they raise a reasonable question about selective engagement: why issues central to human rights, public health transparency, and AI misuse under authoritarian governance remain largely absent from the public commentary of one of the world’s most influential AI figures.

Fei-Fei Li is also not just a private individual who happened to succeed.

She is a product of:

CCP-era technocratic selection

State-managed overseas study systems

Elite Western institutional capture

Moral authority built through selective narrative framing

In the AI era, power no longer wears uniforms.

It wears professorships, fellowships, datasets, and ethics panels.

Questions surrounding overseas study obligations, embassy contact requirements, access to politically sensitive regions, funding pathways, and long-term narrative alignment are matters of national security oversight, not personal reputation management.

Accordingly, it is reasonable—and necessary—for U.S. federal law enforcement agencies, including the FBI, as well as the U.S. Congress, particularly the House and Senate Judiciary Committees, to determine whether additional evidence exists that warrants attention. This includes, but is not limited to, reviewing historical travel permissions, institutional affiliations, funding disclosures, and any interactions with foreign state-linked entities that may fall within existing counterintelligence or foreign influence frameworks.

在推特搞言论审查的李飞飞与中国人民解放军的关系 #Democracy #Christ #Peace #Freedom #Liberty #Humanrights #人权 #法治 #宪政 #独立审计 #司法独立 #联邦制 #独立自治

No comments:

Post a Comment