Recent public discussions have raised new questions about how X (formerly Twitter) handles speech related to China, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and COVID-19 origin research. These concerns revolve around possible influence within X’s technical and moderation infrastructure, particularly regarding employees on H-1B visas and the company’s opaque algorithmic processes.

Recent public discussions have raised new questions about how X (formerly Twitter) handles speech related to China, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and COVID-19 origin research. These concerns revolve around possible influence within X’s technical and moderation infrastructure, particularly regarding employees on H-1B visas and the company’s opaque algorithmic processes.

These issues deserve transparent answers—especially when they involve potential foreign influence on an American social media platform that has enormous impact on global political communication.

1. Claims raised by Dr. Lawrence Sellin

Retired U.S. Army Colonel Dr. Lawrence Sellin recently stated:

He stopped posting about “Anti-American activities of the Chinese Fifth Column in the U.S.” largely because, according to him, pro-CCP Chinese H-1B employees at X used algorithmic tools to suppress his account and reduce his follower count.

According to Central Organization Department notice No.15 of 1984 (组通字〔1984〕15号):

Chinese personnel abroad—students, researchers, and laborers—may have their party membership managed and supervised by their original unit or by overseas party committees.

Crucially, the notice states:

“Each overseas embassy or consulate party committee may, based on the number and distribution of party members and the circumstances in the host country, establish party branches, party groups, or maintain individual contacts.

Given the complexity of foreign situations, overseas party committees are urged to strengthen management and education of party members, assigning full-time or part-time cadres to carry out party work. Among students and labor personnel abroad, formal or temporary party organizations should be established wherever possible to enhance contact with members.”

Implication:

Chinese employees at foreign companies—including H1B visa holders at X—could be formally organized under CCP structures, creating internal oversight, enforcement of party discipline, and coordinated political alignment.

This establishes a systemic, institutional pathway for CCP influence inside foreign enterprises.

Hiring Pro-CCP Chinese employees introduces systemic censorship risk, which may extend to content on other sensitive topics, including corporate fraud or geopolitical matters.

Combined with CCP organizational guidance, these employees could coordinate oversight internally, effectively establishing a party-like structure within X, reinforcing algorithmic censorship with organizational control.

Dr. Sellin’s claim adds to a growing number of public concerns regarding political influence inside X’s workforce.

The public deserves clarity about whether employees with potential conflicts of interest have access to sensitive algorithmic levers that shape visibility, reach, and speech.

2. Public questions regarding Tesla executive Tao Lin (陶琳)

Open-source information shows that Tao Lin, now a Tesla global vice president, previously worked for China Central Television (CCTV)—one of the main propaganda arms under the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department.

Tao Lin (陶琳), Tesla Global Vice President – A Career Overview

Tao Lin currently serves as Tesla’s Global Vice President, responsible for government affairs, public relations, marketing, and branding in Greater China. Previously, she was Tesla’s China Regional Vice President and China Public Affairs General Manager.

Her career prior to Tesla includes roles at Baidu and Renren, as well as positions in Chinese state media, including Central China Television (CCTV) and Wuhan Television, where she worked as a reporter, producer, and director. Reports suggest that her tenure at CCTV played a significant role in her subsequent appointment to Tesla, highlighting her media background as a career asset.

She joined Tesla in January 2014, initially managing China’s government and public affairs. By 2020, she had been recognized as a “Shanghai Model Worker,” reflecting professional acknowledgment of her contributions. Her career trajectory—from local TV to CCTV, to tech companies, and finally to Tesla’s executive ranks—illustrates a combination of ambition, persistence, and adaptability.

Publicly available personal details are limited, though she maintains a Weibo account under the name “Grace Tao Lin”. Her educational background includes an MBA from Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management, completed while working in media.

Tao Lin received the “Shanghai Model Worker” (上海市劳动模范) designation in December 2020. While such awards may appear as professional recognition, the official selection process is highly regulated and politically guided. According to Shanghai Government Notice Number 4 of year 2020 (沪府〔2020〕4号), the award was part of a five-year selection cycle, consistent with the government directive:

“In order to vigorously promote the spirit of model workers in the new era, the spirit of labor, and the spirit of craftsmanship, and to fully leverage exemplary figures, the municipal government conducts the Shanghai Model Worker (Shanghai Advanced Worker) and Model Collective selection every five years. The following guidance applies to the 2015–2019 cycle.”

The December 2020 announcement reflects this structured, five-year process, not a standalone annual award. The selection is governed by the following framework:

Political and ideological criteria: Candidates must demonstrate loyalty to the People’s Republic of China, uphold the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party, support the socialist system, and adhere to official ideological frameworks, including Xi Jinping Thought, Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory, the “Three Represents,” and the Scientific Outlook on Development. Compliance with the directives of the 19th Party Congress and its plenary sessions, as well as alignment with the “Four Consciousnesses,” “Four Confidences,” and “Two Safeguards,” is mandatory.

Organizational vetting: Recommendations are subject to review by multiple government authorities depending on the candidate’s sector. For enterprise executives, reviews include taxation, market regulation, auditing, disciplinary inspection, ecological/environmental oversight, emergency management, and human resources/social security. Economic performance and integrity audits are part of the evaluation. For candidates from foreign-invested enterprises or individuals in foreign-related units, opinions from the foreign affairs authorities are additionally required, highlighting political oversight beyond internal corporate performance. Economic performance and integrity audits are also part of the evaluation.“推荐对象为涉外单位和个人的,须征求外事等部门意见”

Selection committee composition: The municipal selection committee is chaired by the Mayor, with vice chairs including the vice-chair of the Municipal People’s Congress Standing Committee, the Municipal Federation of Trade Unions chair, and a deputy mayor. Members include representatives from municipal party, government, and professional departments, covering areas such as propaganda, organization, law enforcement, economic planning, finance, education, science and technology, public security, human resources, ecology, and more. The committee’s office, located within the Federation of Trade Unions, executes nominations, evaluations, and awards, reporting directly to the municipal party committee and government.

Implication: Receiving the award does not solely reflect professional competence. It signals political alignment and approval by multiple layers of Shanghai’s municipal government and CCP apparatus. Any discussion of Tao Lin’s career achievements, including her Tesla role, should be contextualized within this structured, politically guided recognition system.

Observers have raised questions such as:

Does Tao Lin maintain any professional or political connections with CCTV or the CCP propaganda system after leaving?

Could former media affiliations affect how Tesla or X interact with China-related narratives?

Why did CCTV/CMG interview her in a segment explicitly aligned with the mission of “telling China’s story well” (讲好中国故事), praising the PRC government?

These questions are rooted in publicly accessible information, but they remain unanswered.

3. Relationship between Tesla and X

There are connected transactions between Tesla and X.

While the scope of transactions is not fully explained in filings, the relationship raises reasonable questions about whether cross-company operational links influence moderation decisions on X—especially on China-sensitive topics.

Given China’s critical importance to Tesla’s supply chain and market access, transparency is essential.

4. Questions regarding COVID-19 origin censorship

Multiple researchers, writers, and whistleblowers continue to report suppression of COVID-19 origin content on X.

For example:

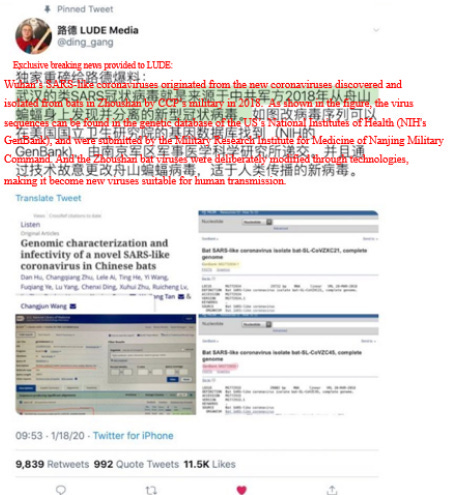

Users claim that X has restricted or shadow-suppressed accounts discussing early origin disclosures, including the account @ding_gang, whose owner proactively requested reinstatement but it was not restored.

Critics argue that this moderation pattern aligns with the CCP’s longstanding pressure to control narratives about the pandemic’s beginning—an issue that has caused millions of deaths and trillions of dollars in global economic losses.

If X wishes to maintain credibility as a “free speech platform,” it must publicly clarify:

Who inside the company has authority to suppress or elevate COVID-19 origin-related content?

Are any employees in positions of influence potentially vulnerable to pressure from foreign governments?

What safeguards exist to prevent foreign political interference?

5. Broader concerns about political influence inside X

Taken together, these issues paint a troubling picture of possible foreign political leverage within X’s algorithmic governance:

Allegations by independent researchers about pro-CCP influence.

Former CCP-linked media personnel now in senior roles at companies operationally connected to X.

Ongoing censorship reports on topics Beijing aggressively seeks to control.

Lack of transparency about who inside X controls algorithmic suppression tools.

All of them raise legitimate questions that Musk and X leadership should answer.

Tao Lin’s career trajectory, CCP-recognized awards, and Tesla role illustrate her alignment with CCP directives, which is relevant when evaluating political influence in foreign-affiliated companies.

The CCP’s overseas party organization framework provides a structural pathway for political supervision in companies like X.

Elon Musk’s hiring of Pro-CCP H1B employees introduces systemic risks of algorithmic censorship and internal party-style oversight, potentially exposing X to serious legal and ethical scrutiny regarding freedom of speech and platform governance.

Conclusion: Transparency Is the Minimum Standard

X cannot claim to be the global defender of free speech while credible public allegations of political manipulation go unaddressed.

The public deserves:

A transparent audit of X’s moderation and ranking systems

Disclosure of employee access tiers, especially for foreign nationals

Clear policies guarding against influence from any foreign government

Restorations or explanations for accounts allegedly suppressed after raising China-related concerns

Free speech requires public trust, and public trust requires accountability.

Elon Musk should address these issues openly.

“X is a private company” is not a legal shield when actions intersect with U.S. criminal or national-security law.

Some may argue that X, as a privately held company, can moderate content as it wishes. But U.S. law draws a clear line:

Private ownership does not excuse conduct that interferes with federal investigations, obstructs truthful information in matters affecting public health and national security, or facilitates foreign influence operations.

Under U.S. statutes, several categories of liability can arise if a platform — intentionally or through willful negligence — helps suppress information relevant to COVID-19 origins:

1. Obstruction of Justice (18 U.S.C. §1505 / §1512)

If a platform knowingly alters, deletes, or suppresses material that could influence federal inquiries — including congressional or executive-branch investigations into pandemic origins — it can constitute obstruction.

2. Conspiracy to Defraud the United States (18 U.S.C. §371)

If private actors collaborate, directly or indirectly, with a foreign government to impede lawful government functions — such as public-health investigation, intelligence assessment, or congressional oversight — this statute can apply.

3. Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA)

If content decisions are influenced by individuals acting under direction, control, or pressure from a foreign government (including the CCP), those individuals — and potentially the company — may have disclosure obligations.

Failure to register, if required, is a felony.

4. Material Support to a Foreign Adversarial Influence Operation

While not always charged directly, federal prosecutors treat coordinated suppression of high-value information (e.g., pandemic origins) as potential support for foreign interference campaigns.

Intent matters, but patterns of algorithmic suppression led by employees vulnerable to foreign leverage would be a red flag.

5. Civil liability in wrongful-death and economic-damage litigation

COVID-19 caused millions of deaths and trillions of dollars in losses.

If a platform is found to have intentionally assisted in suppressing early warnings or whistleblower accounts, it may face claims in tort law, even if the company is private.

Bottom line:

Being a private company does not grant immunity when the issue touches U.S. national security, foreign interference, or the largest public-health catastrophe in a century.

If X allowed employees aligned with or influenced by a foreign propaganda system to restrict COVID-19-origin discussion, the question is no longer “content moderation.”

It becomes one of federal legal exposure.

No comments:

Post a Comment