Introduction

In recent years, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has broadcasted a series of military exercises involving chemical warfare capabilities. These are not obscure rumors or foreign allegations. Instead, they come from the CCP’s own propaganda arms, including outlets like the People’s Daily, Xinhua, China Military Online, and CGTN. Ironically, in their efforts to boast about "readiness" and "modernization," these releases inadvertently document violations of international law—most notably the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), the Geneva Protocol, and the Rome Statute.

This article examines how these exercises constitute potential violations, based on publicly available Chinese reports, and outlines the legal consequences under international treaties.

CCP Reports Confirm Real-Agent Chemical Drills

In multiple military drills, the CCP’s official outlets have confirmed the use of live chemical agents ("实毒") and full-scale battlefield simulations involving decontamination, detection, and hazardous response procedures:

-

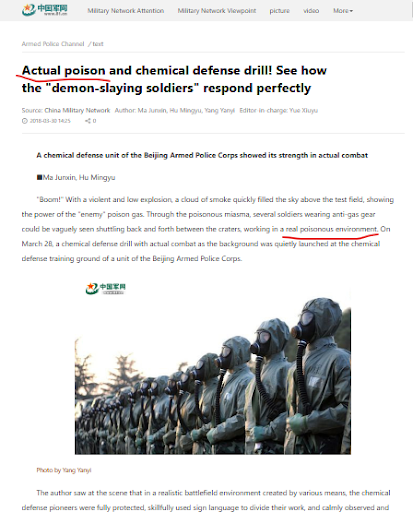

China Military Online (81.cn) published a 2018 report titled “实毒防化演练!看‘降魔神兵’如何应对” confirming that live-agent chemical warfare drills have become “normalized” in PLA Chemical Defense units. Troops operated in toxic environments with simulated agent plumes and emergency leaks. Source (81.cn)

-

A 2014 People’s Daily (military.people.com.cn) report titled “解放军防化部队采用实毒作业 训练像打仗” (PLA chemical defense units adopt real-agent operations; training like actual war) described how troops performed “实毒侦毒” (live-agent detection) and “实毒作业训练” (live-agent operational training) using a stepwise protocol to rapidly identify and respond to chemical exposure.

Source (People’s Daily) -

In 2015, People’s Daily further reported: “济南军区防化兵技能集训紧贴实战 侦毒作业全程使用实毒”, describing a 23-day high-intensity live-agent drill under "toxic mists" and simulated explosions.

Source (People’s Daily)

These reports establish that China’s armed forces, including its specialized chemical warfare units, have trained under real toxic conditions for years.

Such statements confirm that China’s military doctrine includes practical, real-agent chemical warfare preparation.

Legal Framework and Violations

1. Chemical Weapons Convention (1992)

Article I: States must never develop, produce, acquire, stockpile, or use chemical weapons.

Article II(9): Defines chemical weapons to include any toxic chemical used for military purposes.

Violation: Training with real agents for offensive/defensive use qualifies as both development and preparation for use.

2. 1925 Geneva Protocol

Prohibits use of chemical and biological weapons in armed conflict.

Though adopted pre-CWC, customary international law now interprets this as banning use in peacetime preparation too.

Violation: No distinction exists under international law between wartime and peacetime use when it comes to real-agent exposure.

3. Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

Article 8(2)(b)(xvii): War crime to employ poison or poisoned weapons, including chemical agents.

Article 7(1)(k): Crime against humanity to intentionally cause great suffering or serious injury to mental or physical health.

Violation: Civilian exposure during drills, or use without international notification, could qualify under these articles.

No Exemption for "Defensive Drills"

Some may argue the drills are defensive or precautionary. However:

The CWC does not permit real-agent use under the label of “defense.”

Article X permits assistance and protection but not deployment in secret real-agent scenarios.

The OPCW Verification Annex requires inspections and transparency for any real-agent activity.

CCP’s secrecy violates both the spirit and letter of these provisions.

Civilian Harm and Lack of Consent

China has no independent judiciary, no civilian oversight of the military, and no right to information or protest. This removes any possible claim that citizens exposed to drills are informed or protected by law.

The use of 实毒 (real poison) without public disclosure violates not only CWC obligations but also Articles 3, 5, and 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—treaties and declarations forming part of the International Bill of Human Rights.

Conclusion: Propaganda as Confession

The CCP’s propaganda doesn’t exonerate—it incriminates. In boasting about "实战演练 (real combat drills)" and "实毒 (real toxin)," the regime inadvertently provides the evidentiary foundation for future prosecutions under international law.

These drills are not neutral—they represent:

Violation of the Chemical Weapons Convention

Breach of the Geneva Protocol

Evidence of war crimes and crimes against humanity under the Rome Statute

For Chinese citizens and global security alike, these revelations demand serious legal and diplomatic consequences.